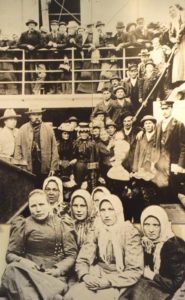

Today is Saint Patricks’ Day, a celebration of Irish heritage. Saint Patrick’s Day began, of course, as a religious holiday. But time and customs have transformed it over the years into a pageant of culture; a chance to acknowledge the contributions that Irish-Americans have made to the US. It is estimated that as many as 4.5 million Irish arrived in America between 1820 and 1930. Between 1820 and 1860, the Irish constituted over one third of all immigrants to the United States. They were brought over in ships packed to the brim with men, women and children all in search for a better life. Most of the immigrants were farmers who had lost most of their profit due to the decline in crop production. Many men came over here alone because they could not afford to bring their whole families with them.

Irish immigrants arriving circa 1840.

The trip over would have been brutal, if they could have afforded it. If they were strong enough to survive the harsh journey over, depending on the amount of money they were able to bring over with them, they could have bought small plots of land and attempt to start their own farms. For those who did not have enough money to start their own farms, it was necessary that they find jobs in order to supply for their families. With the transportation industry expanding and the Industrial Revolution in full swing, America was in need of the extra muscle power.

The Irish filled the most difficult and dangerous jobs, often being paid very little. They dug canals and trenches for water and sewer pipes. Many Irish women became servants or domestic workers, while many Irish men labored in coal mines and built railroads and canals. Railroad construction was so dangerous that it was said, “[there was] an Irishman buried under every tie.” The Western and Atlantic Tunnel was constructed by many of these Irish-American immigrants, without them the tunnel may not have existed.

Irish railroad workers

One famous female Irish immigrant was Mary O’Connell, known as Sister Anthony. She played a role in nursing during the Civil War. Born in Limerick, Ireland in 1814, she immigrated to Massachusetts with her family when she was young. She became a nun at 21, and later served as the head of nursing at St. John’s Hospital in Cincinnati. Soon after the Civil War began in 1861, city leaders asked Sister Anthony if a group of nuns could help ease the suffering of soldiers afflicted by a measles outbreak at a Union Army camp. This mission would lead to even more service, as the nuns spent the war traveling with the Army, ministering to soldiers in hospitals and on battlefields. During her service, Sister Anthony pioneered the technique of battlefield triage, saving lives more efficiently by allocating treatment among patients to maximize survival rates. The technique remains a critical practice in war zones and among disaster relief workers. For her innovation, and her compassion for Northerners and Southerners alike, Sister Anthony would receive praise from President Lincoln, and earn a nickname, “Angel of the Battlefield.”

Sister Anthony, from an 1897 publication.

The Irish men and women who immigrated during the 1800’s played a huge part in sculpting American history and building many parts of country. They were often met with adversities that made living here difficult. Despite these obstacles, doors were opened for the Irish, and generations hence, and the Irish have made an indelible mark on the country.