On the night of April 6th, 1862, a shadowy character named James Andrews walked into the Third Division headquarters and introduced himself to Union General Ormsby Mitchel. They met to discuss what would eventually become one of the most well-known events of the Civil War, the Great Locomotive Chase. This daring plan was originally called “Andrews’ Raid”.

Andrews, a long time Union sympathizer who was a spy in search of personal profit, proposed that he and his “raiders” should be authorized to wreck the Western & Atlantic Railroad in exchange for a large amount of money. This plan helped Mitchel immensely, since his division was planning on capturing the important rail hub in Chattanooga. Disabling the W&A Railroad, would make his job much simpler. If the railroad was taken out of commission, Chattanooga would be cut off from the south and the city would be an easy target. To surprise the enemy, Mitchel and Andrews agreed to synchronize their actions for April 11. Andrews selected volunteers from 3 regiments under Mitchel’s command. He asked specifically for a few soldiers who could handle a locomotive. Three men were picked specifically as a result: Private William Knight, Corporal Martin Jones Hawkins, and Private Wilson Brown all had experience on railroads. They were given civilian clothing and told to travel in small groups. They were to reassemble in Marietta, GA., on April 10 and hijack a train for Chattanooga the following morning. Their plan was to hijack a train headed north, then along the way tear up tracks, cut telegraph lines, and burn bridges.

Illustration some of the men involved in the Great Locomotive Chase—seventeen Union soldiers and two railroad employees who chased them.

They did have a fall back plan in case of trouble. It was to act as Confederate civilians traveling to enlist, they would then enlist in a nearby Confederate unit, and eventually find a way to escape back to Union lines. This actually had to be put into action very quickly; as two raiders were questioned heavily on the way to Chattanooga and had to enlist in a Confederate artillery unit to avoid detection.

Heavy rains delayed their plans by a day. On the morning of April 12th, they woke up and met in Andrews’ room to go over their plans. They would board a combination passenger-freight train named the General, and when the train stopped at Big Shanty, now known as Kennesaw, GA, for breakfast they would uncouple the cars and take the engine. In the end, only twenty of the group ended making the raid—Hawkins, one of the key men, overslept and missed the group’s departure. This was detrimental to Andrews’ plan because Hawkins was the most experienced engineer and was supposed to be in charge of the engine once they stole it.

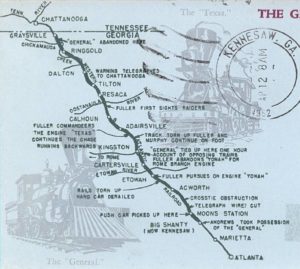

Map of The Great Locomotive Chase from a 1962 souvenir cover marking the centennial of the chase.

When the train stopped in Big Shanty, the passengers and train crew disembarked and went inside The Lacey Hotel to eat breakfast. Andrews’ men proceeded to ready the engine while Knight detached the baggage and passenger cars from the train. They decided to keep the three box cars attached to the locomotive—if they were questioned their story was that they were an emergency ammunition train needed at Corinth by way of Chattanooga, which would explain why they were rushing north with no passengers. Having made their preparations, Knight took control of the engine with Andrews, Wilson climbed into the first boxcar to serve as brakeman, and the others piled into the last boxcar.

Locomotive and tender in front of Lacey Hotel, Kennesaw.

The train crew had just begun to eat when they heard the sounds of the engine and saw it start to pull away from the station. A local resident rode off toward Marietta, and the nearest telegraph station, to alert authorities. William Fuller, the General’s conductor, knew the train would be long gone before the word went out. Fuller took off after the train on foot, followed by his engineer, Cain, and Anthony Murphy. The “Great Locomotive Chase” had begun.

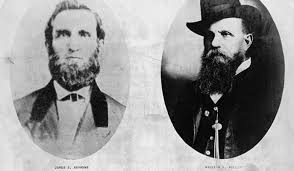

James J. Andrews (right) and William Allen Fuller (left), two participants in the ‘Great Locomotive Chase’ of 1862

Check back next week for the details of the “Chase”!! Interesting side note: The Lacey Hotel was owned and operated by Clisby Austin’s son-in-law. Many of you might recognize the name Clisby Austin, as he was the man who built “Meadowlawn” or the Clisby-Austin House. You can visit the House and learn more about this daring adventure when you come visit us here at the Tunnel Hill Heritage Center.