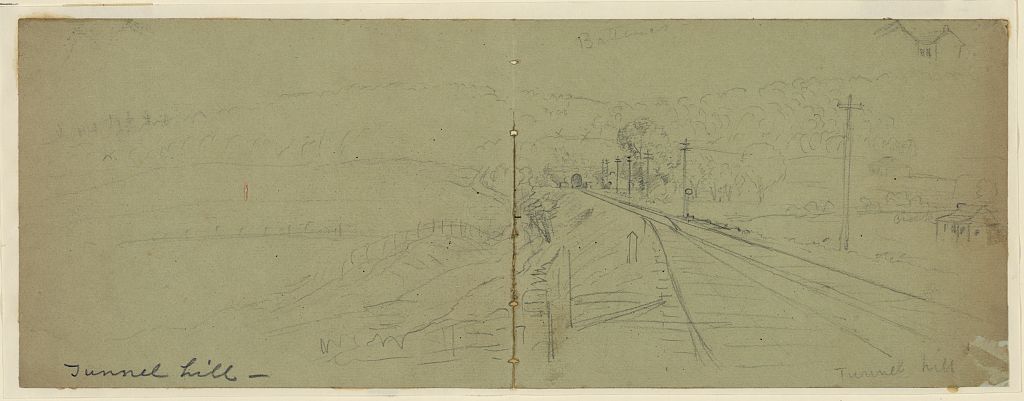

Alfred Rudolph Waud was born October 2, 1828. He was a British-born American illustrator whose lively and detailed sketches of scenes from the Civil War, which he covered as a press correspondent, captured the war’s dramatic intensity and furnished him with a reputation as one of the preeminent artist-journalists of his era. He even sketched Tunnel Hill and other surrounding areas. Waud died in 1891 in Marietta, Georgia, just south of us, while touring battlefields of the South.

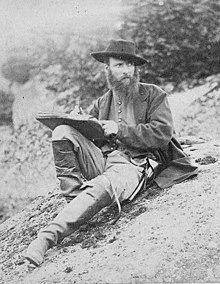

Alfred Waud photographed in 1863 by Timothy H. O’Sullivan sitting in Devil’s Den after the Battle of Gettysburg.

Alfred sailed from London for New York in 1850 aboard the ship Hendrik Hudson. Before immigrating, Waud had entered the Government School of Design at Somerset House, London, with the desire to become a marine painter. Unfortunately, this never came to pass, but as a student, he also painted theatrical scenery. Alfred intended to continue that work in the United States, seeking employment with actor and playwright John Brougham. Waud became an American citizen on January 10, 1870. He married Mary Gertrude Jewell, a native New Yorker, and they had 2 children. They lived in Orange, New Jersey, where they raised their family. In the 1850s, he worked sometimes as an illustrator for a Boston magazine, the Carpet-Bag, and provided illustrations for books such as Hunter’s Panoramic Guide from Niagara to Quebec (1857).

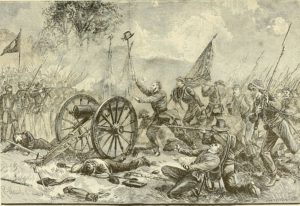

Waud is best known for his Civil War battlefield sketches. The period during the American Civil War was a time when all images in a publication had to be hand drawn and engraved by skilled artists. Photography existed but there was no way to transfer a photograph to a printing plate since this was before the invention of the halftone process for printing photographs. Photographic equipment was too cumbersome and exposure times were too slow to be used on the battlefield. Waud would do detailed sketches in the field, which were then rushed back to the newspaper office who employed him. There engravers would use the sketches to create engravings on boxwood. Since the blocks were about 4 inches across they would have to be composited together to make one large illustration. The wood engraving was then copied via the electrotype process which produced a metal printing plate for publication.

Tunnel Hill, Waud, Alfred R. (Alfred Rudolph), 1828-1891, artist, Title inscribed lower level and lower right.

New York Illustrated News hired Waud as an illustrator (a full-time paid staff artist) in 1860. In April 1861, the newspaper assigned Waud to cover the Army of the Potomac, Virginia’s main Union army. He first illustrated General Winfield Scott in Washington, D.C., and then went on to sketch the First Battle of Bull Run in July. Waud joined Harper’s Weekly toward the end of 1861, continuing to cover the war. He was one of two artists that witnessed and sketched the Battle of Gettysburg. His depiction of Pickett’s Charge is thought to be the only visual account by an eyewitness.

The American Civil War was the first major conflict to be “observed” by the general public while it was occurring and it became the first great media event in American history. Families at home demanded news and pictures of the battles and the life that their loved ones were enduring. So, this gave Waud ample opportunity to put his talent to use. Artists were usually paid by the sketch, $5.00 to $25.00 per picture on the average. Well known and established artists were sometimes given a regular salary, Waud had this type of set up with Harper’s Weekly.

Artists, like Waud, experienced the same dangers and hardships as the soldiers and when captured they were imprisoned. One artist wrote of waking in the morning to find the soldier sharing his tent dead. He had stopped a bullet that would have also killed the artist. Alfred Waud actually had Confederate sharpshooters fire at him repeatedly while sitting in a tree to sketch a battle.

An engraving of Pickett’s charge at Gettysburg by Alfred Waud.

In May 1864, Theodore Lyman wrote of Waud: “Friend Waud is along and with us still and sojourns with the Engineers. He draws for Harper’s Weekly, very good sketches he sends them, and very poor woodcuts they make thereof. His indignation has, long since given place to sarcasm; for W. is a merry & philosophic Bohemian!” [Lowe, Meade’s Army (2007), pp. 166-167]

Waud’s keen eye and deft pencil strokes were the means by which many Americans experienced episodes of the Civil War and visualized the cities and towns of mid-America. Waud has two sketches that involve our history here at the Tunnel Hill Heritage center. He sketched our famous Western and Atlantic Railroad Tunnel as well as the infamous locomotive “The General”. This week’s blog is dedicated to him since his birthday is on Friday. How far we have come from hand drawn battle scenes, to now being able to view live action on our cell phones.

Sketch from the front of a railroad engine named “The General.”