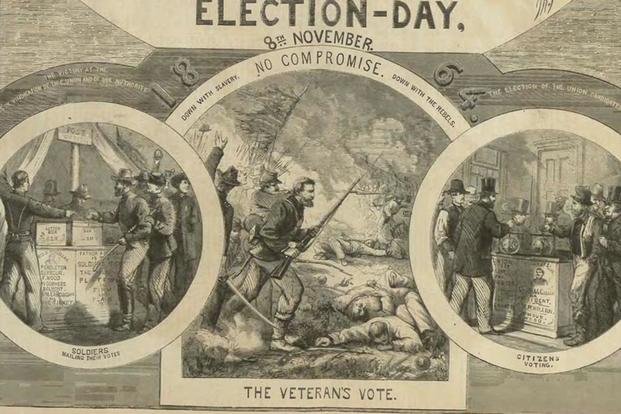

Have you ever wondered how mail-in voting started? Early records show that in Massachusetts, men could vote from home if their homes were “vulnerable to Indian attack,” according to historian Alex Keyssar’s book The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States. But it was during the Civil War that America first tried out absentee voting on a large scale. The reasoning was that so many of the men who were eligible to vote were away fighting in other areas across the country. During the 1864 presidential election, Union soldiers voted in camps and field hospitals, under the supervision of state officials. The Confederate states held their own election. From Kentucky to Vermont, voting rights were extended to those far away from the polls for the first time. It did have many skeptics and raised concerns about the validity of the votes cast.

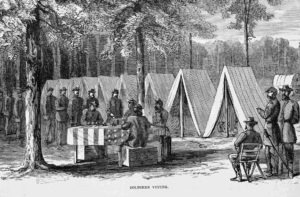

During the Civil War, typical voting processes were replicated on battlefields of 14 states. Here, an illustration shows Union Army soldiers lined up to vote on November 8, 1864.

Overall, about 150,000 out of 1 million soldiers were able to vote by mail. Since Lincoln won the popular vote by more than 408,000 votes—and the electoral vote with 212 over McClellan’s paltry 21—it’s unlikely those absentee ballots actually swung the election in his favor, but they did set the precedent for expanded absentee voting laws for wars (and pandemics) in years to come.

The states which Lincoln won in the election of 1864 are shown in red. McClellan won Kentucky, New Jersey, and Delaware. Notice that citizens of the Confederacy did not vote in the election.

It was Secretary of War Edwin Stanton’s idea to create an absentee voting system. He agreed with Lincoln’s principles that a democratic society fighting for its life should include all the legal voters who wished to vote. He instituted a system that was ultimately left up to the states to regulate but allowed soldiers deployed to the front lines to vote in their local, state and federal elections. In Democratic states, like Indiana, they did not allow soldiers to vote in their army camps. But the War Department kind of encouraged commanders to let these soldiers go home for a week or something in order that they could vote. Twenty-five states would change their laws to allow soldiers to vote while away, either at a field station in their military encampment or by mail. Everyone else had to be tethered to their local polling place. The new voting procedures also created confusion. New rules that were being tried for the first time and carried out in different ways would determine the fate of the nation.

Lincoln ended up winning 78% of the military’s vote and 55% of the popular vote. Lincoln even won areas of the Confederacy occupied by the Union Army that allowed citizens to vote. Historians should be cautious in interpreting what this figure means about the sentiments of the North’s fighting men, said Jonathan White, an assistant professor of American studies at Christopher Newport University. “It doesn’t mean that the soldiers were as committed to emancipation as the numbers suggest.” Mr. White, who has written extensively on the soldier vote, suggests that “some white soldiers were not willing to vote for Lincoln because they thought he was an abolitionist; others were unwilling to vote for McClellan because they thought he was a Copperhead,” the derisive term for Democrats and other Northerners who sympathized with the South. Instead of voting for “the lesser of two evils,” they refused to vote at all. Which is often something, we still see in today’s society.

Soldiers reading postings about the 1864 election.

It is often said that the election of 1864 was one of the most important in American history. No one knows how important Tuesday’s election will be seen in the long sweep of the nation’s life. But the two elections, separated by 150 years, do offer a vantage point from which to take a measure of our democracy and to judge for ourselves whether it still merits to be called, in Lincoln’s words, “the last best hope of earth.”