Today we will learn about Susie King Taylor. She like, Ann Bradford Stokes, overcame slavery and made her mark upon history. She was a teacher, nurse, and advocate for human rights. Susie was the only black nurse to publish a memoir of her wartime experiences. This blog explores her story in celebration of Black History Month.

Today we will learn about Susie King Taylor. She like, Ann Bradford Stokes, overcame slavery and made her mark upon history. She was a teacher, nurse, and advocate for human rights. Susie was the only black nurse to publish a memoir of her wartime experiences. This blog explores her story in celebration of Black History Month.

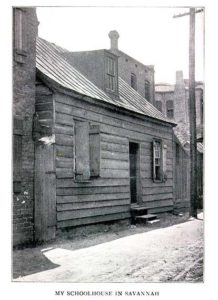

In 1848, Susie King Taylor was born as Susan Ann Baker, the first of nine children. Her parents were slaves on the Grest plantation in Liberty County, Georgia. The Grests had no children of their own and treated the Baker children with great kindness. Later this influenced how Susie viewed relationships between the races. When she was seven, the Grests allowed Susie and her brother to move to Savannah and live with their grandmother, a freed slave. It was illegal to educate black children during this time, but her grandmother was determined for them to have an education and sent them to a neighbor who ran a secret school in her home. They and other students had to hide their books and go in and out of the house one by one to avoid suspicion. Susie’s illegal education ended with the arrest of her grandmother for singing freedom hymns. Susie and her brother were sent back to their family.

Susie’s private school in Savannah, Georgia, circa 1902.

Contribution: UNC-Chapel Hill Library

Susie was only 13 when the Civil War broke out. She and her family escaped to freedom on St. Simon’s Island off the Georgia coast, then occupied by Union troops. Impressed with her ability to read and write, commanding officers offered her an opportunity to organize a school for the former enslaved. She was the first African-American teacher for freed slaves, and taught the children as well as adults until the island was evacuated in October 1862.

While teaching and living on St. Simon’s, Susie married Edward King, a black army sergeant who was with the 33rd Regiment, U.S. Colored Troops. She became a part of the regiment and was given the job as laundress. But quickly earned more responsibilities because of her education and skills. In 1863, she traveled with the regiment nursing the sick and wounded. She used a combination of traditional and folk remedies she learned from her great-grandmother, who was a noted midwife. Taylor knew how to prepare and administer medicinal roots and herbs — knowledge that served her well as a nurse. She also came up with clever solutions when food ran out. She wrote about a time there was little feed her patients, so she mixed turtles’ eggs with condensed milk to make “a very delicious custard.” Susie also learned to defend herself against possible enemies: “I learned to handle a musket very well while in the regiment, and could shoot straight and often hit the target. I assisted in cleaning the guns. I was also able to take a gun all apart and put it together again.”

King’s experiences as a black employee of the Union Army are recounted in her diary. She describes numerous battles and intersperses these accounts with personal stories and commentary on life in the South, and the unequal treatment of the African American soldiers:

“The first colored troops did not receive any pay for 18 months and the men had to depend wholly on what they received from the commissary… their wives were obliged to support themselves and their children by washing for the officers and making cakes and pies which they sold to the boys in the camp. Finally in 1863, the government decided to give them half pay, but the men would accept none of this. They preferred rather to give their services to the state, which they did until 1864, when the government granted them full pay, with all back due pay.”

Though she was never paid for her service, King wrote:

“I was very happy to know my efforts were successful in camp, and also felt grateful for the appreciation of my service. I gave my services willingly for four years and three months without receiving a dollar. I was glad, however, to be allowed to go with the regiment to care for the sick and afflicted comrades.”

When the war was over, Susie and her husband, Edward, moved back to Savannah, Georgia, where she opened a school for the freed slave children. In September 1866, Edward died unexpectedly not too long after their first child was born. Susie continued to support herself and her newborn son with a small teaching salary. In the early 1870’s, King traveled to Boston as a domestic servant of a wealthy white family. Free schools had been established in Georgia at this point and she could no longer earn income by teaching. She had to leave her son with her mother in Georgia to pursue this opportunity, something she hated to do.

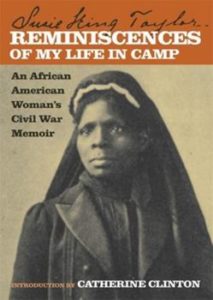

Modern Cover of Her Book

While in Boston, she met Russell Taylor, also a Georgia native. They married in April 1879, in Liberty County, Georgia. However, Susie lived in Boston for the rest of her life, returning to the South only occasionally. She wrote her autobiography “Reminiscences of My Life in Camp with the 33rd United States Colored Troops Late 1st S.C. Volunteers”, after a trip to Louisiana in the 1890s to care for her dying son. It was privately published in 1902. It is the only known published recollection of the experiences of an African American nurse during the Civil War. Regardless of her work during the Civil War and her dedication to political and social reform, Taylor died relatively unknown in 1912. She is buried next to her second husband at Mount Hope Cemetery in Roslindale, Massachusetts.

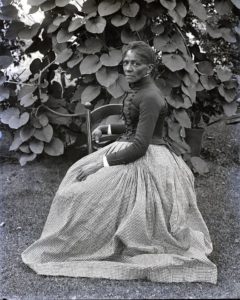

“Powerful and Determined”: Susie King Taylor

Contribution: Stephen Restelli

Taylor concluded her memoir with both hope and a demand: “my people are striving to attain the full standard of all other races born free in the sight of God, and in a number of instances have succeeded. Justice we ask, –to be citizens of these United States, where so many of our people have shed their blood with their white comrades, that the stars and stripes should never be polluted.”

Susie King Taylor’s story is not well known, it should be though! She overcame much and did so without bitterness, instead served with a grateful heart. Susie has much in common with Kate Cummings, another Civil War nurse that we feature in the Clisby Austin House because of her work around our county. I enjoy learning these unique stories and can’t wait for our special reenactment tour coming up in March where we will tell stories like this! Come out and visit us for yourself and see.

Erected by the Georgia Historical Society, Waters Foundation, Inc. and the Susie King Taylor Women’s Institute & Ecology Center

2019