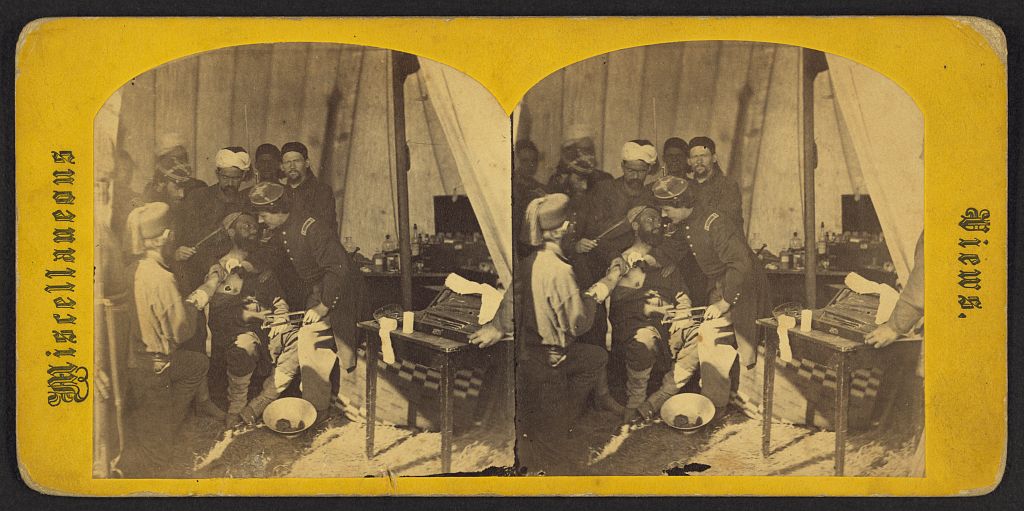

“The limbs of soldiers are in as much danger from the ardor of young surgeons as from the missiles of the enemy.”

Surgeon Julian John Chisholm, 1864

Although the exact number is not known, more than half of the operations performed during the Civil War, were amputations. That’s roughly 60,000 severed hands, feet, arms, and legs. The death rate for limb amputation was about 28%, which made it preferable to just treating the wound. Amputation was intended to prevent deadly complications such as gangrene. It was often performed without anesthesia, and sometimes the patient suffered from painful sensations in the severed nerves. Overall, the removal of a limb was widely feared by soldiers.

The most common wounds suffered by Civil War soldiers were from the bullets fired by muskets. The typical bullet fired was called a Minie ball, a conical bullet with hollowed grooves. When it struck a human, the ball caused considerable damage, many flattening upon impact. Minie balls splintered bones, damaged muscle, and drove dirt, clothing, and other debris into the wounds. The damage done by Minie balls is largely the reason for so many amputations.

Minié balls (via Wikimedia Commons)

While both armies received criticism for the number of amputations performed, they saved many lives and there could have been way more casualties than there were. The badly torn tissues where bullets had entered nearly always became infected. And as we discussed previously the main cause of casualties during the Civil War were infections and disease. The missiles would break through the skin carrying with them dirty material into the fractures. The fractures were defined as “compound” and the bones broken into many fragments were called “comminuted”, both of which are terms that are still used today. These types of fractures became perfect breeding grounds for bacteria and bone infections that inevitably caused death if limbs were not amputated. Even today the only way to treat these is with prolonged use of antibiotics that didn’t exist to Civil War surgeons at this time.

Human distal femur shot with a 510-grain lead Minié ball fired from a .58 caliber Springfield Model 1862 rifle.

The chances of survival for an amputation depended on what limb was amputated and how fast medical treatment was administered after the wounding. Many amputations over the Civil War occurred at the fingers, wrist, thigh, lower leg, or upper arm. The closer the amputation was to the chest and torso, the lower the chances were of survival as the result of blood loss or other complications.

After completing numerous amputations after a battle, doctors had another problem. What to do with the piles of discarded limbs? A pile of amputated limbs frightened many, and helped feed the idea that surgeons were more “butchers” instead of “doctors”. After the Battle of Fredericksburg, the poet Walt Whitman described the scene of at a Federal hospital at Chatham just across the Rappahannock River:

“Outdoors, at the foot of a tree, within ten yards of the front of the house [probably the still standing Catalpa tree], I noticed a heap of amputated feet, legs, arms, hands, etc. — about a load for a one-horse cart. Several dead bodies lie near, each covered with its brown woolen blanket. In the dooryard, toward the river, are fresh graves, mostly of officers, their names on pieces of barrel staves or broken board, stuck in the dirt.”

Unfortunately, a clear answer doesn’t exist. Not surprisingly little was written about the subject probably because it was such a sickening sight. Some archaeological evidence found on several battlefields show that many amputated limbs were buried in mass graves or sometimes burned. The struggle of the sight of amputated limbs was not only found at the hospitals, but soldiers had to confront this stigma at home as well.

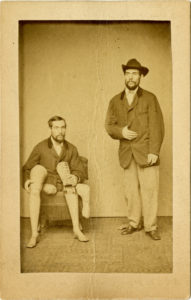

Alfred A. Stratton of Co. G, 147th New York Infantry Regiment in uniform, with amputated arms

Library of Congress

The Civil War created thousands of “maimed men” who returned home with empty sleeves or missing legs. These men not only had to learn how to function without a limb, they also had to come to terms with how they were treated by their family and friends. In the 1800s, one of the signs of manhood was the ability to support one’s family. Having a disability meant that these men were no longer the leader of their families, but instead had to rely on others. Back then, men who were not the breadwinners in their home had negative implications put on their moral character, and thus were often looked down on in society. The negative prewar stigma related to the loss of limb and the ability to work, many soldiers not only opposed the amputation before the surgical procedure began, but struggled with depression, shamefulness, and finding a meaningful role in society again after returning home.

A. A. Marks advertising card, showing a customer holding and wearing his artificial legs, late 1800s

Courtesy: Warshaw Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

Like many aspects of Civil War medicine, because there were so many cases of amputations, the procedures, recovery methods, quality of prosthetics, and an increased awareness for mental health were all driven into today’s modern medicine. The pain of the past has helped us grown and learn. Here at the Tunnel, we even have our own amputation history. General John Hood recovered at the Clisby Austin House after his leg was removed. Rumors say that his leg is in fact buried somewhere on the grounds. We have built our own mini memorial to it that can be found near the General Store. Come visit us and see if you can find it!