Rose Greenhow was a society woman in D.C. who became a spy ring leader and icon for the Confederacy during the Civil War. The first major Confederate victory on the battlefield, was owed in part, to the work of Rose O’Neal Greenhow. Today, we will learn about this infamous spy for the Confederacy and how she used her femininity to an advantage.

She was born Maria Rosetta O’Neal around 1813 in Maryland to plantation owner John O’Neal and his wife, Eliza. She earned a childhood nickname of “Wild Rose” that stuck with her through her whole life. When she only four, her father was killed by one of his slaves. To help ease her financial burden, Rose’s mother sent her to live with her aunt, Maria Ann Hill in Washington D.C. She ran a prominent boarding house at the Old Capitol Building. A steady stream of influential people staying at the boarding house, helped Greenhow quickly learn the ways of society and politics. Pretty, lively, and intelligent, Rose was popular with the members of Congress who boarded with her aunt, and she had several suitors. Rose married Robert Greenhow Jr., a wealthy bachelor who had trained as a physician but ultimately became an official in the United States Department of State. The Greenhows had four daughters. Their youngest child was named Rose O’Neal Greenhow and was nicknamed “Little Rose”. Robert’s work with the State Department prompted the family to move with him to Mexico City in 1850 and then to San Francisco, California. In 1852, Greenhow returned East with her children, a journey that took months. Her husband died in an accident in San Francisco in 1854. However, being a widow did not disrupt Greenhow’s popularity in the capital.

Rose O’Neal Greenhow and “Little” Rose, in the courtyard of Old Capitol Prison in D.C., where she was being held on suspicion of treason in 1862.

After losing her husband, Greenhow became more sympathetic to the Confederate cause. Greenhow was an advocate for secession and “preserving the Southern way of life,” including slavery. She was strongly influenced by her friendship with U.S. Senator John C. Calhoun from South Carolina. In her own words:

“I am a Southern woman, born with revolutionary blood in my veins, and my first crude ideas on State and Federal matters received consistency and shape from the best and wisest man of this century, John C. Calhoun.”

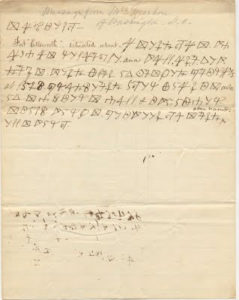

Greenhow’s loyalty to the Confederacy was noted and she was recruited as a spy in 1861. Her recruiter was U.S. Army captain Thomas Jordan, he set up a Confederate spy network in Washington. He supplied her with a 26-symbol cipher for encoding messages.

Ciphered message from Mrs. Greenhow of Washington D.C.

Henry Wilson, who was on the Senate Military Affairs Committee, gave Rose a tip that the Union Army planned to advance on Manassas, Virginia. Rose drafted Bettie Duvall, a young Southern sympathizer, to help her warn the Confederate troops. Rose wrote a cipher and hid the note in Duvall’s hair. Duvall, dressed as a poor farmer woman, made her way to Confederate-occupied Fairfax Court House, Virginia. The suspicious Confederate commanders eventually allowed her to speak. Bettie unraveled her hair and revealed the secret message. With this information, the Confederate army was able to fully prepare for the Federal attack. This engagement, which became known as the First Battle of Manassas, was a Confederate victory.

Greenhow’s spy network went on to span several states and included 48 woman and two men. These conspirators included her dentist, Aaron Van Camp, and the prominent D.C. banker William Smithson. The network used a sophisticated cipher to code and decode messages. Rose was brilliant at collecting information, but careless about storing information. She kept copies of messages sent to Beauregard in decoded form, maps of the Union fortifications, and other incriminating documentation in her home. This misstep eventually lead to her discovery by Allan Pinkerton, head of the Union Secret Service. Rose was placed under house arrest with “Little” Rose. Other raids were conducted in DC in the following weeks and suspected spies were imprisoned in Rose’s home. The house became known as “Fort Greenhow.”

United States Old Capitol Prison, ca. 1860 – ca. 1865

On May 31, 1862, Greenhow and her daughter were released without trial, on condition she stay within Confederate boundaries. She and her daughter went on to Richmond, Virginia, where Greenhow was hailed by Southerners as a heroine. President Jefferson Davis welcomed her return and enlisted her as a courier to Europe. Greenhow traveled through France and Britain building support for the Confederacy with the aristocrats. She even had audiences with Queen Victoria and Napoleon III. While in Europe, Greenhow wrote her memoir, titled My Imprisonment and the First Year of Abolition Rule at Washington. She published it in 1863 and it sold many copies in Britain.

Title Page: My Imprisonment and the First Year of Abolition Rule at Washington

Rose headed back to America in August 1864 aboard the Condor, with $2000 in gold to help aid the Confederate cause. As the Condor drew close to Wilmington, North Carolina the captain spotted Union ships. Attempting to escape the ships, the Condor became grounded. Greenhow, worried about being captured, got into a rowboat and started paddling toward shore. The rowboat capsized. Weighted down by the gold and her hoop skirts, Rose drowned. When her body washed ashore, they found on her, a copy of her memoirs and a note to her daughter Rose:

“You have shared the hardships and indignity of my prison life, my darling; and suffered all that evil which a vulgar despotism could inflict. Let the memory of that period never pass from your mind; else you may be inclined to forget how merciful Providence has been in seizing us from such a people.”

Rose was buried with full military honors by the Confederacy, her body even wrapped in the Confederate flag. After her death, she became a revered symbol for the Confederate cause. Rose used her overlooked position as a woman to her advantage and helped the Confederacy in many ways. Even though she picked a losing cause, her heroic actions and bravery are still amazing.

Greenhow’s grave in Wilmington, North Carolina