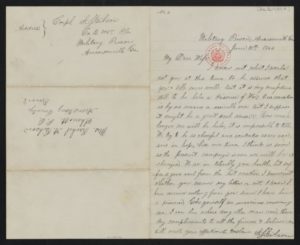

“I don’t know for whom I am keeping this Diary,” Corporal Samuel J. Gibson wrote on August 12, 1864. “I still have hope that I will yet outlive this misfortune of being a prisoner but I am not made of iron.” Gibson was part of the 103rd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment. He kept a diary while a prisoner at Camp Sumter in Georgia. A Confederate prisoner of war camp better known by its geographic name, Andersonville. He wrote a letter to his wife, Rachel, that same day. He assured her that while his condition at Andersonville was “by no means a desirable one,” it “might be a great deal worse.)” He suffered “a good deal from the hot weather…Give yourself no uneasiness concerning me,” he wrote to ease her fears. “I can live where any other man can.”

Gibson’s letter to his wife, dated June 12, 1864.

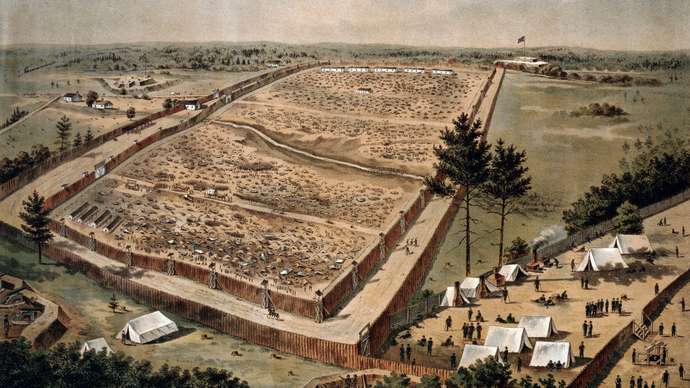

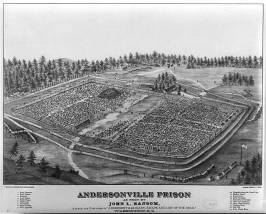

The reality of Gibson’s life at Andersonville was quite different, however. The first prisoners arrived in Andersonville late February 1864. During the next few months, approximately 400 more arrived each day. By the end of June, 26,000 men were penned in an area originally meant for only 10,000 prisoners. During the 14 months it existed, more than 45,000 Union soldiers were confined here. Of these, almost 13,000 died from disease, poor sanitation, starvation, overcrowding, or inadequate housing. During the worst months, 100 men died each day.

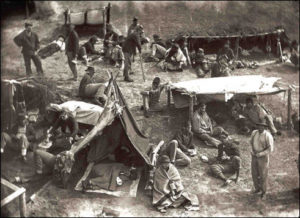

The Confederate government could not provide adequate housing, food, clothing or medical care to their captives because of failing economic conditions in the South, lack of transportation, and the desperate need of the Confederate army for food and supplies. The prisoners arrived before the barracks were built and so lived with basically no protection from the hot Georgia sun or the cold winter rains. The prisoners tried put together their own shelter. The first men gathered up the leftover lumber and scraps from the construction of the prison and built rude huts. However, the wood supply was soon exhausted and the more resourceful Union men erected tents, from odd bits of clothing. Others dug holes in the ground for protection. These, often would collapse when the ground flooded, thus killing the men sleeping in it.

Andersonville prisoners and tents, August 17, 1864

The daily food ration consisted of cornmeal and either bacon or beef. Occasionally, peas, rice, vinegar, and molasses were provided. Food was usually issued uncooked because the kitchen facilities were not completed by the time the prisoners arrived. The rations were minimal because the Confederate army needed what was available to feed their soldiers. The only water supply was a stream that first ran through a Confederate army camp, then pooled to form a swamp inside the stockade. It provided the only source of water for drinking, bathing, cooking, and sewage. Sergeant Clark N. Thorp writes about the lack of food in his diary:

“If cooked rations were issued we would get a piece of corn-bread about 2” x 2” x 3,” the meal being ground cob and all, coarser than one in the north would buy for his horse, a few beans (perhaps one-half pint) and a couple of ounces of pork or bacon….”

The poor conditions were not overlooked by the Confederates. Captain Henry Wirz was the commander in charge of Andersonville. Wirz recognized that the conditions were inadequate and petitioned General Winder to provide more support. These petitions fell on deaf ears as Winder’s opinion was that all Union soldiers should die. In July 1864, Captain Wirz sent five prisoners to the Union with a petition written by the inmates asking the government to negotiate their release. The Federal government stopped prisoner exchanges because they believed it was helping the Confederates bolster their army. The request in the petition was denied and the Union soldiers, who had sworn to do so, returned to report this to their comrades. After the war ended, Wirz was found guilty of war crimes related to Andersonville and was hung as a result.

Confederate Captain Henry Wirz

National Park Service

Planning an escape was routine among the prisoners. The men formed units to burrow out of the camp using tunnels. The locations of the tunnels would aim towards nearby forests fifty feet from the wall. The most difficult part was not the tunneling but the surviving after. It was nearly impossible due to the poor health of prisoners. Prisoners caught trying to escape were denied rations, chain ganged, or killed. Playing dead was another method of escape. The death rate of the camp made disposing of bodies a relaxed procedure by the guards. Prisoners pretended to be dead and then would be carried outside of the walls to a pile of dead bodies. As soon as night fell the men would get up and run.

Andersonville Prison by John L. Ransom, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

After 15 months of operation, the camp was liberated in May of 1865. Some prisoners had been released previously and taken by a Union ship back North. As news Andersonville reached the newspapers, Northerners were newly enraged at the South and its army. Hearing of the miserable conditions and high death rate in the camp, Walt Whitman wrote, “There are deeds, crimes that may be forgiven, but this is not among them.”

You can now visit Andersonville and see the remains of the prison. The site also includes a prisoner of war museum and a national cemetery where Union soldiers who died at the camp are buried. The National Prisoner of War Museum opened in 1998 as a memorial to all American prisoners of war. Both Elmira and Andersonville prisoners faced atrocities that no person should, the lessons learned from that still echo in today’s prisoner of war camps.

Replica of Camp Sumter, Andersonville National Historic Site, Georgia.