Almost 200 years ago, General Benjamin Dudley Pritchard and the 4th Michigan Cavalry effectively ended the Civil War. It was May 10, 1865 when they captured Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederate States of America, outside Irwinville, Georgia. It’s an event that many historians consider to be the ultimate end of the Civil War conflict. Richmond had fallen, Robert E. Lee had had surrendered at on April 9. The interesting part of Jefferson’s capture isn’t that it officially ended the war. However, it is the story surrounding his attire.

Courtesy: Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries

Davis and some of his Cabinet retreated from Richmond after General Lee’s defeat on April 2, 1865. Davis’ plan was to escape by sea from Florida and sail to Texas where he hoped to establish a new Confederacy. The Cabinet had taken gold from the Confederate treasury. They were nervous that the ex-Confederate troops would come searching for them to steal the gold since they knew the war was over. They also were on the run from the Union army who wanted to capture Davis and earn the $100,00 bounty offered by the Federal government.

On May 9, Davis decided to make camp for the night near Irwinville. They pulled off the road, and the pine trees helped conceal their position. President Davis’s escort did not circle their wagons. The thought was that if Federals surrounded them while camped in a tight circle, it would be difficult for Davis to escape. So, Davis’s party pitched camp with an open plan, scattering the tents and wagons over an area of about 100 yards. For reasons unknown, they had no guards that night, even though they faced a genuine threat of attack from either ex-Confederate soldiers looking for gold or Union cavalry on the hunt for Davis.

Davis told his aides that he would leave the camp sometime during the night. He was dressed to travel: a wool frock coat of Confederate gray; gray trousers; high black leather riding boots, and spurs. His horse was saddled and ready to ride. When the Union soldiers invaded around 3 am, Jefferson Davis mistook them at first for the expected ex-Confederate soldiers. He opened the tent flap and realized quickly the Federal troops were there to capture him.

Wedding photograph of Jefferson Davis and Varina Howell, 1845

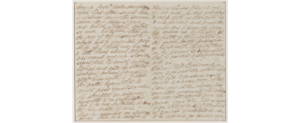

When apprehended by the Union soldiers, Davis was wearing his wife’s dark gray cloak and black shawl. First Lady Varina Davis gave him her cloak because it was a waterproof material. She hoped it might camouflage his clothes, which resembled a Confederate officer’s uniform. Below is an excerpt from a letter she wrote to her friend explaining his odd dress.

“Knowing he would be recognized, I pleaded with him to let me throw over him a large waterproof which had often served him in sickness during the summer as a dressing gown, and which I hoped might so cover his person that in the grey of the morning he would not be recognized. As he strode off I threw over his head a little black shawl which was round my own shoulders, seeing that he could not find his hat.”

Letter (pages 13-20), Varina Davis to Montgomery Blair describing the capture of her husband, Jefferson Davis, 6 June 1865.

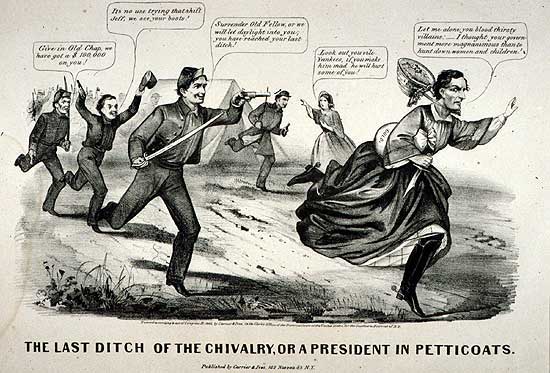

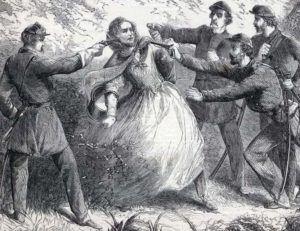

News spread of Davis’s capture—and with it the story of him dressed in women’s clothes. Even the great showman P. T. Barnum tried to make a profit off of the story. He wanted the clothes to display in his NYC museum and was prepared to pay handsomely. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton denied his request and the garments were brought to Washington D.C. The arrival of the “petticoats” proved to be a big letdown. When Stanton saw the clothes, he knew instantly that Davis wasn’t wearing a hoop skirt and bonnet when captured. The public was clamoring to see the women’s clothes, however public viewing would expose the lie that Davis had worn one of his wife’s dresses. So, Stanton hid the clothes to perpetuate the myth that the cowardly “rebel chief” had tried to run away in his wife’s clothes.

The image of the Confederate president masquerading as a woman entertained Northerners but outraged Southerners. Eliza Andrews, a young woman who had witnessed Davis pass through her town, during his escape, condemned the pictures in her diary:

“I hate the Yankees more and more, every time I look at one of their horrid newspapers . . . the pictures in Harper’s Weekly and Frank Leslie’s tell more lies than Satan himself was ever the father of. I get in such a rage . . . that I sometimes take off my slipper and beat the senseless paper with it. No words can express the wrath of a Southerner on beholding pictures of President Davis in woman’s dress.”

Capture of Jefferson Davis at Irwinsville, GA: Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, June 3, 1865

Davis and his family were taken by ship, along with Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens, to Fort Monroe, Virginia. On May 22, Davis was taken ashore and placed in prison. He was indicted on the charge of treason but was never tried, and was released two years later, in May 1867. He survived Lincoln by 24 years, wrote his memoirs, and became the South’s most beloved living symbol of the Civil War. Although he devoted the rest of his life to preserving the memory of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis could never dispel the myth of his capture dressed as a Southern belle. In 1939, Jefferson Davis Memorial Historic Site was opened to mark the place where Confederate President Jefferson Davis was captured.

Monument at Jefferson Davis Memorial Park.