When the Civil War began in 1861, Tennessee was the final state to secede and join the Confederacy. It did so despite the objections of residents in the eastern part of the state, who voted against secession. This is a story of amazing independence — the story of the Free & Independent State of Scott.

When Abraham Lincoln was elected President of the United States in 1860, the writing was on the wall. War was happening. Tennessee was hesitant to join the Confederacy, despite the lobbying of its governor, Isham Harris. Harris urged secession even before Lincoln was elected, warning that the “reckless fanatics of the north” would require Tennessee to leave the Union. Residents in the eastern part of Tennessee were strongly opposed to secession, while residents in the western part strongly desired it. Harris called a referendum vote in February 1861.

The vote surprisingly failed. In Scott County, 93% of voters cast their ballots against secession: 385-29. It’s questionable that Scott Countians voted in defiance of slavery. It’s likely that the hard-working people in a very remote corner of the world simply wanted to be left alone — and wanted the United States to remain intact.

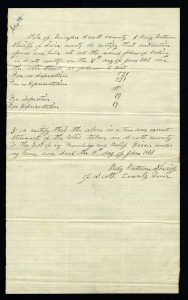

Scott County’s vote certification after the June 1861 secession referendum.

Gov. Harris valiant in his desire to secede rallied another referendum vote in June 1861. By that time, the Battle at Fort Sumter had marked the start of war. President Lincoln had called for volunteers to crush the Southern rebellion, and Tennesseans mindset shifted. When the second referendum was tallied on June 8, 1861, East Tennessee remained strongly opposed to secession, but the vote passed. In the days prior to the vote, U.S. Sen. Andrew Johnson delivered a fiery speech against secession on the steps of the Scott County Courthouse. This time, 97% of Scott Countians voted against secession. The tally was 521 to 19.

Scott County’s first courthouse, built in 1851. Where Andrew Johnson delivered a speech against secession on June 4, 1861.

East Tennesseans were furious over the state’s vote to secede. They petitioned Gov. Harris to allow the eastern portion of the state to secede and form a state of its own. Harris refused, and in response sent troops to suppress any attempts of rebellion. Scott Countians did not care one bit and held a special session in Huntsville, passing a proclamation declaring its independence from Tennessee.

County leaders said they knew they didn’t have legal rights to secede from Tennessee, but they also claimed that Tennessee didn’t have the ability to legally secede from the United States. They declared themselves the Free & Independent State of Scott. In response, Gov. Harris sent 1,700 soldiers to Scott County to arrest and hang all members of the county court. They retreated after meeting resistance, and none of the members of the court were ever captured.

Scott County paid a price for its independence. It was subject to guerrilla warfare and lawlessness. Farms were raided by Confederate forces and Union forces alike. No major battles fought here, but there were several minor skirmishes. County historian Paul Roy noted in his book, Scott County in the Civil War:

“Men and boys hid out in the woods to avoid being conscripted into the service, while women and children had to assume their duties on the farm. Anything of value, real or emotional, had to be hidden away in the ground, a hollow tree, or under a rock ledge for fear that it would be taken. Families were often hard-pressed to keep food from being taken as soldiers marching through Scott County were always foraging for food, both for themselves and for their horses. On those rare occasions when great numbers of soldiers came through the county, farmers along the major routes would lose everything — their crops in the field for food for the soldiers, fodder for their horses and mules, and rail fences for their firewood.”

Amazingly, Scott County would remain an unofficial sovereign entity for 125 years until 1986, when it was readmitted to the state of Tennessee by a formal resolution. That summer, as part of Tennessee’s Homecoming celebration, Scott County Commission adopted a resolution that read, “After 125 years of independence, in this the year of Tennessee homecoming, the Scott Commissioners and people of Scott have declared the Free and Independent State of Scott to be dissolved.” Governor Lamar Alexander signed the resolution, officially readmitting Scott County to Tennessee. Such an interesting and relatively unknown part of Civil War history.