Memorial Day was born out of need after the Civil War. A war-torn United States was faced with the task of burying and honoring the 600,000 to 800,000 Union and Confederate soldiers who had died in the bloodiest military conflict in American history. The first national commemoration of Memorial Day was held in Arlington National Cemetery on May 30, 1868, where both Union and Confederate soldiers are buried. Many cities across America claim to have observed their own earlier versions of Memorial Day or “Decoration Day” as early as 1866. It was called Decoration Day originally because of the practice of decorating the graves.

In the late 1990s, an outstanding discovery was made in a dusty Harvard University archive. Historians learned about a Memorial Day commemoration organized by a group of African Americans freed from slavery less than a month after the Confederacy surrendered in 1865.

In the late stages of the Civil War, the Confederate army transformed the posh Charleston Racetrack (or country club) into a makeshift prison for Union soldiers. Around 260 Union soldiers died from disease and exposure while being held in the race track’s open-air infield. Their bodies were quickly thrown in a mass grave behind the grandstands. When Confederate troops fled the badly damaged city after it fell to the Union army, the now free slaves remained. One of the first things those emancipated men and women did was to give the fallen Union prisoners a proper burial.

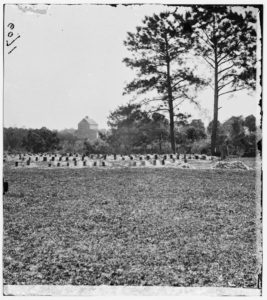

April 1865 photograph of the racetrack gravesite. Courtesy: Civil war photographs, 1861-1865, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Around two dozen African American Charlestonians reorganized the graves into rows and built a 10-foot-tall white fence around them. An archway overhead spelled out “Martyrs of the Race Course” in black letters. On May 1, 1865, about 10 days later they held a huge event to give the soldiers a proper funeral. According to two reports found in The New York Tribune and The Charleston Courier, a crowd of 10,000 people, mostly freed slaves with some white missionaries, staged a parade around the race track. Starting at 9 a.m., about 3,000 black schoolchildren paraded around the race track holding roses and singing the Union song “John Brown’s Body,” and were followed by adults representing aid societies for freed black men and women. Members of the famed 54th Massachusetts and other Black Union regiments were in attendance. The crowds sang patriotic songs like “America” and “We’ll Rally around the Flag” and “The Star-Spangled Banner.” After the dedication the crowd dispersed into the infield and did what many of us do on Memorial Day: enjoyed picnics, listened to speeches and watched soldiers drill.

Clubhouse at the race course where Union soldiers were held prisoner. Courtesy: Civil war photographs, 1861-1865, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

The New York Tribune described the scene as “a procession of friends and mourners as South Carolina and the United States never saw before.” The gravesites looked like a “one mass of flowers” and “the breeze wafted the sweet perfumes from them” and “tears of joy” were shed. If the news reports are accurate, the 1865 gathering at the Charleston race track would be the earliest Memorial Day commemoration on record. The only other mention of the race track event was in a 1916 correspondence sent from a women’s Civil War historical society in New Orleans to its sister chapter in Charleston, asking about a big parade of freed slaves on a horse track at the end of the war.

“I regret that I was unable to gather any official information in answer to this,” wrote the Charleston society’s president, S.C. Beckwith.

Eventually, the old horse track and country club were torn down, and thanks to a gift from a wealthy Northern patron, the Union soldiers’ graves were moved from the humble white-fenced graveyard in Charleston to the Beaufort National Cemetery. The story of the first Memorial Day faded into memory until the findings during the 1990s.

Alfred Waud illustration of the Union soldiers cemetery known as “Martyrs of the Race course” in Charleston, S.C. Courtesy: Morgan collection of Civil War drawings at the Library of Congress

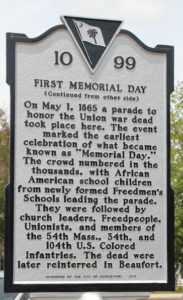

In 1966, former President Lyndon B. Johnson declared Waterloo, New York to be the official birthplace of Memorial Day. Then, in 1971, Congress established “Memorial Day” as an official federal holiday to honor all Americans who have fallen in U.S. Wars. Charleston officials have taken steps towards recognizing the city’s African-American history. Following a community campaign, the city of Charleston held its first formal commemoration of the African-American roots of Memorial Day in 2010, and the following year it established a plaque. Whether it was truly the first Memorial Day ceremony, and what influence it might have had on later observances, are still matters of contention. Regardless, what a great tribute the African-American people gave to the soldiers that might have been forgotten.

Plaque Honoring the Celebration in Charleston, SC.