Can you imagine what it would be like to be arrested and taken 1000’s of miles from your home just because you worked for a company that someone else had a disagreement with? That’s exactly what happened during the Civil War to women and children who worked for the Roswell Manufacturing Company in the cotton and woolen mills. One of the great almost unknown tragedies of the Civil War is the story of the Roswell Mill Women. Many folks living in metro Atlanta think of General William T. Sherman and the city’s 1864 burning when the Civil War is mentioned. But months before that, Sherman ordered his men to destroy mills in Roswell and to arrest about 400 women who were working in them. He arrested them and had them sent North as prisoners and traitors. There is little evidence showing that any of these women returned home, many of them died on the long journey North.

“The Bricks,” two apartment buildings totaling ten units, were erected circa 1840 as housing for mill workers in the Roswell mill village.

As the Union forces approached Atlanta in the early summer of 1864, almost all the members of the founding families of Roswell—aristocrats from the Georgia coast, most of them owners and/or stockholders of the Roswell Manufacturing Company mills—had fled. The remaining residents were mostly the mill workers and their families. The two cotton mills and a woolen mill continued to operate, producing cloth for Confederate uniforms and other much-needed military supplies, such as rope, canvas, and tent cloth.

On July 5, seeking a way to cross the Chattahoochee River and gain access to Atlanta, Brigadier General Kenner Garrard’s cavalry began the Union’s twelve-day occupation of Roswell, which was undefended. Theophile Roche, a French citizen, had been employed by the mills. In an attempt to save the Roswell Manufacturing Company mills during the Union occupation of Roswell, he flew a French flag in hopes of claiming neutrality.

However, the letters “CSA” (Confederate States of America) were found on cloth being produced. On July 7, 1864 after it was proven that the claim of being neutral was false, General Sherman wrote to General Garrard: “I repeat my orders that you arrest all people, male and female, connected with those factories, no matter what the clamor, and let them foot it, under guard, to Marietta, which I will send them by cars to the North…The poor women will make a howl.”

Just off Roswell Square on Sloan Street is a small city park amid what remains of the mill quarters. In that park is a marble column that appears to be broken off. In Victorian iconography the broken column memorial signified a life cut short or somehow unfulfilled. This was put up in 2000, to honor the women taken from Roswell.

Mill workers, women, their children and a few men were rounded up on the square, arrested and charged with treason. They were transported by wagon to Marietta and imprisoned in the Georgia Military Institute. Then, with several days’ rations, they were loaded into boxcars that proceeded through Chattanooga, Tn. headed to Louisville, Ky., the final destination for many of the mill workers. Others were sent across the Ohio River to Indiana. First housed and fed in a Louisville refugee hospital, the women later took what jobs and living arrangements could be found. Those in Indiana struggled to survive, many settling near the river, where eventually mills provided employment. There was little probability of a return to Roswell, so the remaining women began to marry and bear children.

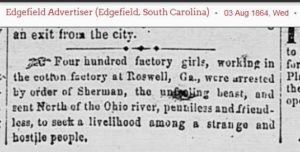

South Carolina newspaper clipping

The tragedy, widely publicized at the time, with outrage expressed in northern as well as southern presses, was virtually forgotten over the next century. Only in the 1980s did a few writers begin to research and tell the story. Even then, the individual identities and fates of the women remained unknown. One of the women involved in this tragedy was pregnant and working as a seamstress at the mill. Adeline Bagley Buice was sent north to Chicago and left to fend for herself. It would take five years before she and her daughter would return, on foot, to Roswell. Her soldier husband returned to Roswell after the war. Thinking that his wife must be dead, he remarried before she returned. This one of the very few stories we know about the 400 women who disappeared.

Mary Kendley married a man from Perry County and stayed in Indiana.

Why was this story lost in history? The majority of the workers were illiterate and did not keep diaries or write letters. The women and children, along with a few men, could not present their case. And so, it was lost for many years until historians sought out the little-known story. As it is with many tragedies, human faith and hope prevailed. These women and children made the best of their situation and survived. Dr. Mary Walker, who is now on display in our museum, was one of the doctors that met the women upon their arrival in Louisville, KY. Come out and see us and learn more about her and other Civil War stories.