On Nov. 18, 1862, Union soldiers outside of Corinth took two men into custody, both dressed in ragged Confederate uniforms. They were promptly placed under arrest. The story provided by these men was too fantastic to believe and so were ushered over to the headquarters of Brig. Gen. Grenville Dodge.

The men stated they were privates, John R. Porter in the 21st Ohio Infantry, and John Wollam in the 33rd. These two had volunteered for a daring mission led by a civilian scout, James J. Andrews. A team of two civilian spies and twenty-two soldiers had set out in early April. We talked about their adventure earlier this year. Andrews Raiders and the Great Locomotive Chase.

When the mission came to a disastrous ending in Ringgold, Andrews told his men that it was every man for themselves. They scattered into the woods, and tried to escape capture by the Confederate army. Hungry, unprepared, wet, and lost, most were captured in short order. Within a week, all the Raiders were captured. They were held in the dreaded Swaim’s Jail in Chattanooga, where Andrews and some of the men tried unsuccessfully to escape. A raider wrote about the terrible prison, “Though the night was cool outside, the heat here was more than that of a tropic noon and the perspiration soon oozed from every pore. The fetid air and the stench made me for a time deadly sick, and worst of all, there was an almost unbearable sense of suffocation.”

Swaim’s Jail. The raiders were confined in the jail’s basement, only 13 square feet and accessed through a trap door and down a ladder.

They eventually learned how to remove their handcuffs, and they made plans for an escape. On the day that the plan was to be carried out, twelve of the group were ordered to Knoxville for a trial. There was a sad departure at Swaim’s Jail as Andrews shook their hands. With a tear in his eye, he told them, “Boys, if I never see you here again, try to meet me on the other side of Jordan.”

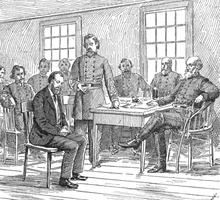

Depiction of the court-martial of one of the raiders in Knoxville

On May 31, as the remaining raiders in Chattanooga were exercising outside, an officer entered the gate. He walked briskly toward James Andrews. He handed him a large envelope. It was the verdict of the court martial after review by Confederacy Secretary of War Leroy P. Walker and President Jefferson Davis. The leader of the Andrews Raiders was found guilty as charged and sentenced to death by hanging. The execution was to take place the following Saturday.

The remaining raiders decided at once to put their plan of escape into operation. However, Andrews was separated from the rest that evening and put into the hole. This made it necessary for the raiders upstairs to cut into the plank floor separating them from Andrews. The work was suspended the next morning, but began in earnest again on Sunday night. They also had to cut the lock on the door before bringing Andrews up. Once they did that, Andrews was lifted up on a rope made by twisting their clothes together. Lastly, they had to carefully pick their way along a brick wall and make a longer rope for the descent to the ground outside the jail.

Andrews escaped first. However, he knocked off a loose brick with his foot and the guards were alerted at once. They began firing at Andrews in the shadowy darkness. He escaped barefoot. John Wollam was the only other raider who escaped from the jail through the gunfire. The other raiders hastily returned to the cell and chained themselves back up.

News of the escape spread like wildfire through Chattanooga, and soon soldiers, civilians and dogs were excitedly joining in the pursuit of the two escaped prisoners. Andrews and Wollam had separated a short distance from the jail. Andrews went just south of town and climbed a tree with dense foliage. When night fell he swam across the river. He lost his coat during the swim and cut his bare feet on the rocks.

Early the next morning, Andrews was observed by a search party while he hid near the area known as Moccasin Bend. He dashed into the woods, and came across a boy in a dugout canoe. Andrews asked the startled boy to row him to Williams Island. After letting Andrews out on the island, the boy paddled down the island to the home of Samuel Williams and informed him about Andrews. Williams thought that it might be one of the escaped prisoners. He was able to find Andrews hiding on the island and confronted him. He brought Andrews into his home, fed him dinner, and gave him some shoes and a new coat. The next morning, Williams took him to the Confederate authorities in Chattanooga. Now that the infamous leader was back in custody, soldiers began building a scaffold for the purpose of hanging James Andrews.

John Wollam headed toward the Tennessee River following his escape from Swaim’s Jail. He dropped his coat and vest by the river, waded out a short distance, then returned and hid out in the canebrake. The search party reached the river and upon discovering Wollam’s clothes, they concluded that the escaped raider had drowned. Later in the night, Wollam made his way along the riverbank until he found a canoe. He took it and began rowing down the river. At dawn, he hid the canoe and waited until nightfall to begin floating the river again. He did this for a week, and then thinking he was in safe territory, he began traveling during the day. However, he was still within Confederate lines. Wollam was captured by a patrol when he was almost to a Union Camp.

Private John Wollam. Civil War Medal of Honor Recipient for action in Georgia in April 1862.

The Confederate command in Chattanooga was no longer going to take any chances of an escape by James Andrews and his Raiders. He was placed back in the hole of Swaim’s Jail, and extra guards were placed on duty. With only four days left to live, Andrews managed to gain some pen and paper in order to write several farewell letters and his will. However, reports came that the Federals were advancing rapidly toward Chattanooga. On the day before the planned execution date, James Andrews was moved to Atlanta. Andrews left Chattanooga for the last time on the early morning train. On June 7, the leader of the Andrews Raiders was taken to gallows a block from Peachtree Street in Atlanta and hanged. Conductor Fuller, who attended the hanging, reported, “He died bravely.”

The trials of the other raiders were delayed by the war, and some eventually escaped. Wollam, Porter, and Hawkins reached Federal lines to the north. The rest were recaptured and later returned in prisoner exchanges. All survived the war, becoming the first recipients of the newly minted Medal of Honor. As a civilian, Andrews was ineligible for the honor.

Medal of Honor awarded posthumously in 1866 to raider John Morehead Scott.

After the war, both sides of the Great Locomotive Chase held mutual reunions until 1906, a few months after Fuller passed away. The last of the participants died in 1923. Their famous locomotives outlived them. The Texas currently resides in the Atlanta Cyclorama Building in Grant Park, and The General, having come full circle, is now the pride of the Civil War museum at Kennesaw, Georgia. Andrews and the other executed raiders are buried at National Cemetery in Chattanooga, where a granite monument, donated by the State of Ohio in 1890, is topped with a bronze replica of The General.

Andrews’ Raiders Monument in Chattanooga, TN. Taken in 2015.

This is the story of the first recipients of the Medal of Honor. How exciting that our Tunnel was part of this event! Come out and see us and learn more facts about the Great Locomotive Chase and the Tunnel they raced through.