With the scars from Gettysburg still fresh in the mind of the Union, attentions were turned on September 18-20, 1863, to the Battle of Chickamauga. Along the Chickamauga Creek in Georgia, Confederate General Braxton Braggs, Union General William Rosecrans and more than 120,000 men came to blows. The casualties were the worst of the Civil War after Gettysburg, with approximately 34,000 men injured, captured or killed, including Mary Todd Lincoln’s brother-in-law. The battle’s outcome would determine who would gain control of Chattanooga, Tennessee, which, at the time, was a crucial railway gateway.

The Battle of Chickamauga by Kurz & Allison

In the upcoming weeks, we will be talking about the events leading up to the Battle of Chickamauga and its significance. This was a large victory for the South, but still did not change the course of the war. Many of the wounded were brought to the Clisby Austin House which was serving as a battlefield hospital. Including John B. Hood, who we feature in the upstairs of the House.

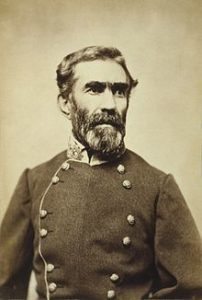

The late summer and early autumn of 1863 were desperate times for the South. General Robert E. Lee’s invasion of Pennsylvania had been repelled at Gettysburg. The Mississippi River was completely in Federal hands following the surrender of Vicksburg and Port Hudson. General William Rosecrans had driven General Braxton Bragg’s army south from Middle Tennessee to the outskirts of Chattanooga but did not advance across the Tennessee River which allowed Bragg to rest his exhausted army.

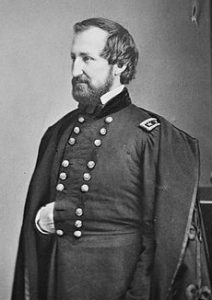

Major General William S. Rosecrans marched his Union Army of the Cumberland out of its defenses at Murfreesboro, Tennessee, on June 23, 1863. His objective was Gen. Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee stationed around the Confederate supply base at Tullahoma near Chattanooga, and thence to capture Chattanooga itself. Chattanooga was key to the North winning the war because it was a large rail center. Rosecrans moved against the Confederates under General Bragg, taking Middle Tennessee and the City of Chattanooga with less than 600 casualties.

William S. Rosecrans

Establishing a headquarters west of Chattanooga (in Bridgeport and Stevenson, Alabama), Rosecrans “consolidated” his position for another six weeks, re-supplying his army from the railhead at Stevenson, Alabama and planning his next move. While Bragg concentrated on the enemy northeast of Chattanooga, Rosecrans slipped the majority of his troops across rugged Lookout Mountain. Caught completely off-guard, General Bragg was forced to withdraw again, this time to Lafayette, Georgia while Rosecrans advanced through mountain passes from Stevenson, Alabama to the city of Chickamauga. Rosecrans goal was to capture the Western and Atlantic Railroad to use as a supply line from Chattanooga.

Perhaps overly confident, Rosecrans believed Bragg’s forces to be in messy retreat and decided to deal the Army of Tennessee a severe blow. He sent three corps into northern Georgia in pursuit of the fleeing army. But the Federal forces traveled on widely separated routes, too far apart to support one another. Unknown to Rosecrans, Bragg halted his retreat and bolstered his army with reinforcements from Mississippi, Knoxville, and Virginia.

Braxton Bragg

On September 17, 1863, the two armies shifted into position along northwest Georgia’s Chickamauga Creek. Weather conditions for men in the field had been hot and dry enough to stir up stifling clouds of dust. But that night, as soldiers steeled themselves for impending combat, the weather suddenly turned cold. A howling north wind blew through the dark creek bottoms and over rolling wooded hills like a bloodthirsty banshee. Having thrown away their blankets in the summer heat, many soldiers on both sides shivered and huddled for warmth. Temperatures dropped into the thirties, not counting wind chill. The vicious two-day battle that followed took place on frosty morning ground under a cold, clear sky. At night, stars twinkled and water froze in canteens. In defiance of orders, many soldiers built fires to keep wounded comrades from freezing to death.

Confederate troops load and fire into the thick underbrush around Chickamauga Creek, which gave the battle its name.

With Bragg in Lafayette at Gordon Hall and Rosecrans at the Lee and Gordon Mansion in Chickamauga, the two rivals were closer to each other than they were to most of their troops. The Union army numbered approximately fifty-eight thousand men, while the Confederates mustered some sixty-six thousand troops; this was one of the few times the Army of Tennessee would fight with a numerical advantage.

All of these circumstances would factor into the oncoming battle on September 18th and 19th. The two armies lined up along the “River of Death” may not have known they were facing the second bloodiest battle of the Civil War. We will delve further into the actual battle with the next blog post. Revealing how General Hood ended up staying at the Clisby Austin house and if Rosecrans’s was successful in his capture of the Western and Atlantic Railway.