Santa in the Camp: Civil War Christmas

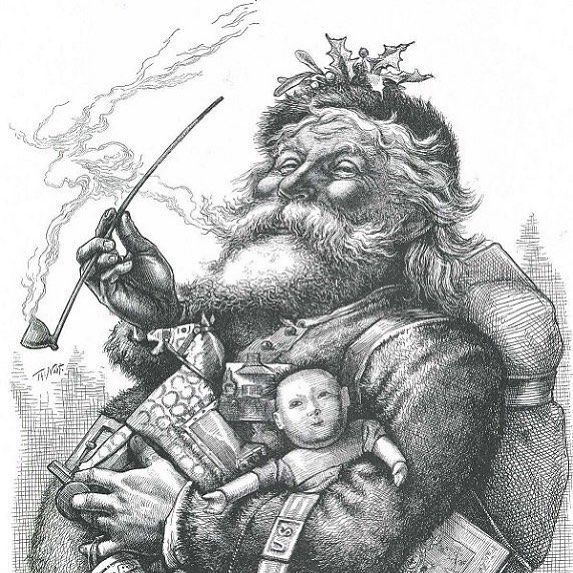

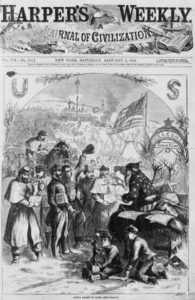

You could call it the face that launched a thousand Christmas letters. Appearing on January 3, 1863, in the illustrated magazine Harper’s Weekly, two images cemented the nation’s obsession with a jolly old elf. The first drawing shows Santa distributing presents in a Union Army camp. Lest any reader question Santa’s allegiance in the Civil War, he wears a jacket patterned with stars and pants colored in stripes. In his hands, he holds a puppet toy with a rope around its neck, its features like those of Confederate president Jefferson Davis.

“Santa Claus in Camp” Harper’s Weekly (1863)

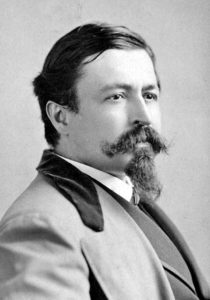

The appearance of our “modern” version of Santa Claus is often attributed to the works of Haddon Sundblom, who drew Santa for Coca-Cola Company advertising beginning in 1931. However, what we consider to be Santa comes from the drawings of Thomas Nast. A Bavarian immigrant, political cartoonist extraordinaire and the person who “did as much as any one man to preserve the Union and bring the war to an end,” according to General Ulysses Grant. Nast tapped his boyhood memories of St. Nicholas to sketch a Santa with a reindeer-drawn sleigh, long white beard and fur-lined hat and coat visiting a Union army camp. Nast’s Santa isn’t decked out in red, however, but a star-spangled outfit featuring red-and-white striped pants and a blue jacket with white stars. Nast enhances the patriotic setting by drawing soldiers firing an artillery salute, the Stars and Stripes flapping proudly in the breeze and a triumphal arch decorated with evergreens. Nast based his Santa’s appearance on Clement Clarke Moore’s 1823 poem “A Visit from St. Nicholas”.

Thomas Nast

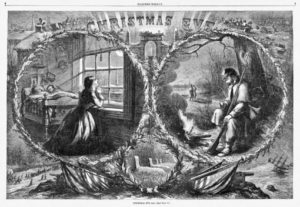

The second drawing features Santa in his sleigh, then going down a chimney, all in the border. At the center, divided into separate circles, are a woman praying on her knees and a soldier leaning against a tree. “In these two drawings, Christmas became a Union holiday and Santa a Union local deity,” writes Adam Gopnik in a 1997 issue of the New Yorker. “It gave Christmas to the North—gave to the Union cause an aura of domestic sentiment, and even sentimentality.”

“Christmas Eve” Harper’s Weekly (1863)

Before the early 1800s, Christmas was a religious holiday. The Industrial Revolution created a middle class that could afford to buy presents, and factories able to mass-produce goods. The holiday began to appear in popular literature, such as Clement Clarke Moore’s poem “A Visit from St. Nicholas” (1823) and Charles Dickens’ book A Christmas Carol (1843). By the middle 1800’s Christmas begin to look much as it does today. However even with the Civil War raging, children received homemade gifts due to the scarcity of materials. Children in the South worried about Santa making it through the Union blockade. In 1864, some Georgia children were told that Santa had been arrested by the Union provost marshals (the Civil War military police). Others were told Santa had been shot by the Yankees!

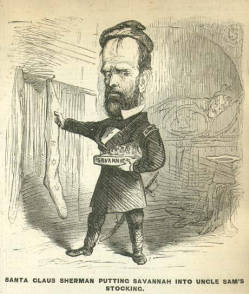

Union and Confederate soldiers swapped coffee and newspapers on the frontlines, and some did their best to decorate the camp. “In order to make it look as much like Christmas as possible, a small tree was stuck up in front of our tent, decked with hard tack and pork, in lieu of cakes and oranges, etc.,” wrote New Jersey Union soldier Alfred Bellard. Perhaps the most famous gift of the Civil War was Sherman presenting President Abe Lincoln with the captured city of Savannah as a Christmas gift on December 22, 1864. He sent the following telegram to Lincoln:

SAVANNAH, GA., December 22, 1864

(Via Fort Monroe 6.45 p.m. 25th)

His Excellency President LINCOLN:

I beg to present you, as a Christmas gift, the city of Savannah, with 150 heavy guns and plenty of ammunition, and also about 25,000 bales of cotton.

W.T. Sherman, Major General.

“Santa Claus Sherman Putting Savannah into Uncle Sam’s Stocking.”

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper

Nast’s early woodcuts of Santa Claus crystallized the modern-day image of a hefty, jolly Kris Kringle with a long white beard and red outfit. Though they varied from year to year, Nast’s Santa drawings appeared in Harper’s Weekly until 1886, amounting to 33 illustrations in total. Unsurprisingly, the drawings from the Civil War often fell solidly in the realm of propaganda; Nast staunchly supported abolition, civil rights and the Republicans.

Even though people may know that Nast gave us the donkey for the Democrats and the elephant for Republicans, few may realize the role he played in shaping modern day Christmas. He created the image of Santa Claus, though we don’t tend to think about Civil War propaganda when we’re opening presents today.