On January 2, 1861, a miserably rainy day, Georgia voters went to the polls and selected delegates to a convention that would decide the state’s response to Lincoln’s election. In many counties the candidates divided along two divergent views. Immediate secessionists advocated leaving the Union without further consideration. Cooperationists, however, tended to be more peacemaking. Their opinions ranged from maintaining a devout Unionism, to desiring a scheme in which the South acted in unison, to advocating a delay of the act of secession. Low voter turnout due to the poor weather may have affected the election’s outcome, but the immediate secessionists finished with a slight majority of delegates.

The state capitol in Milledgeville, pictured circa 1850, housed the General Assembly from 1807 until 1868 and was the site of the state’s secession convention in 1861

The Georgia Secession Convention of 1861 represents the pinnacle of the state’s political sovereignty. With periodic interruptions, the convention met in Milledgeville from January 16 to March 23, 1861, and not only voted to secede the state from the Union but also created Georgia’s first new constitution since 1798. Politically the convention was a watershed event that hastened the Civil War and dramatically changed the course of Georgia history. Georgia’s declaration of causes made it clear: the defense of slavery was the primary cause for dissolving the Union. Georgia was not the first state to secede from the Union. It followed in the footsteps of South Carolina, Florida, Mississippi and Alabama.

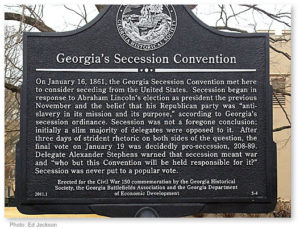

Georgia’s Secession Convention historical marker, erected in 2011 for the Civil War 150 commemoration by the Georgia Historical Society.

Franklin Garrett, a contemporary diarist, wrote: “Georgia pulled out of the Union Saturday the 19th at 2 o’clock, by a vote of 208 to 89. Majority for secession, 119. The cannons were heard on Saturday night [in Atlanta] in honor of the occasion. There are now five states out of the Union. No more fighting in South Carolina heard from and I hope there will not be.”

Governor Joseph E. Brown was a leading secessionist and led efforts to remove the state from the Union and into the Confederacy. A firm believer in state’s rights, he even defied the Confederate government’s wartime policies. He resisted the Confederate military draft and tried to keep as many soldiers at home as possible to fight invading forces. Brown challenged Confederate impressment of animals, goods, and slaves. Brown felt as though Georgians should only be fighting and defending Georgia. Several other governors followed his lead. During the war, Georgia sent nearly 100,000 men to battle for the Confederacy, mostly to the Virginian armies. Despite secession, many southerners in North Georgia remained loyal to the Union.

During the U.S. Civil War, Rabun County was one of only five Georgia counties that did not declare secession from the Union. Although the county was largely untouched by the Civil War, the area did border on anarchy during that time. Glen Kyle, Managing Director of the Northeast Georgia History Center at Brenau University in Gainesville, says a different kind of conflict occurred in the hills, valleys, scattered settlements and farms in this part of the state. It was a different conflict largely because of the independence of the Scotch Irish who settled in the area, he said.

“There wasn’t a unified sense of nationhood for the Confederacy like there was in other parts of the South,” according to Kyle. “Here in the mountainous area there was a very individualistic life style.”

That life style set the stage for incidents in which the mountain folk actually fired upon Confederate authorities seeking men to fight in their armies after the Confederacy established the first military draft in American history. They were focused on their churches, their community, their family and kinship, that’s what their world was. Very few delegates from this mountainous region voted to secede. Fannin, Gilmer, Rabun delegates did not vote for secession. Delegates from more urban areas did vote for secession, they had closer economic ties with the rest of the South. Based on the divided sentiment, there were men who hid out, biding their time until they could travel North and join the Union Army. Some who hid out from the draft were discovered and hung on direct orders from Governor Brown.

So much like Georgian’s today who were divided by a vote, so were Georgian’s in 1861. The state still has much division but hopefully we can come together and work to a better and brighter future. History has much we can learn from and we love to teach at the Tunnel Hill Heritage Center. Book a guided tour today and learn some more little known facts about life during the 1860’s.