When the Civil War broke out, men and boys from all over the country rushed to enlist. Many of these recruits were from rural or small communities. Before the war, these men had never traveled more than twenty or so miles outside of their hometown. They were about to be thrown in with thousands of men who came from different walks of life and had experienced different illnesses throughout their life. As a result, the soldiers were exposed to disease on a level that had never really been experienced before. Because of their relatively sheltered upbringing, many soldiers did not have immunities to common diseases. Childhood illnesses like measles were popping up in these crowded, dirty training camps and the doctors had more than they could handle.

John B. Gordon, a Confederate general, wasn’t oblivious to this trend. He wrote: “It was amazing to see the large number of country boys who never had the measles. They ran through the whole catalogue of complaints that boyhood and even babyhood are subjected. They had everything except teething, nettle-rash, and whooping cough. I rather think some of them were afflicted with the latter disease.”

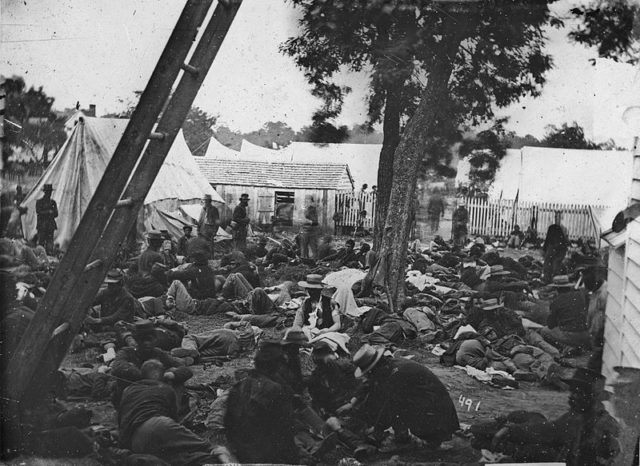

Wounded soldiers gather outside of a field hospital after Battle of the Wilderness in May of 1864.

Soldiers with preexisting conditions like TB were also admitted into the army due to the lack of screening at the time of their enlistment. The majority of the population believed that this would be a very short war and as long as the men could march and carry a gun, they were deemed fit for service. So, men who were just on the edge of becoming ill, or might have been a carrier of some disease, were crammed into tents with a dozen other guys who were then exposed. This did improve as the war went on, recruits were screened more meticulously and denied entry into the army if they were found to be even remotely ill or deficient in some medical way.

Stress and the exertion of marching put a tax on the body and could leave soldiers more vulnerable to disease. Rest was vital to the health of an army and especially those convalescing from illness. Sanitation was also a culprit. Back home on the farm, men would relieve themselves in an outhouse or just anywhere they pleased. With families, that may not be a problem, but when thousands of men are using the bathroom wherever they want, controlling cleanliness was near impossible. Officers in charge of these men didn’t know better, because the general stench of an army camp was common. They thought it was normal for camps to be this filthy and it was considered a “patriotic odor”. Soldiers generally knew that you shouldn’t poop where you get your water. But, they still had the problem of other soldiers contaminating the water upriver, which flowed downriver to other soldiers filling their canteens. This bacterium would then bring on the most rampant disease of the whole war.

Dysentery is an advanced form of diarrhea. Commonly known by it’s nickname the “Virginia Quickstep” and “Tennessee Trots”, it hurt soldiers just as much as bullets would. Soldiers were practically set up for this sickness due to their poor diet while on the march and spoiled rations. Once the bacteria was in the stool, it was able to spread the disease through the army quickly. This disease is no respecter of rank. Even General Robert E. Lee came down with dysentery at one point or another. Out of 1,000 soldiers, 20 would die of dysentery or diarrhea before the war came to its end in 1865.

While the doctors and surgeons had the best of intentions, the soldiers often didn’t trust them or their remedies. Soldiers might turn to home solutions they knew well to combat their diseases, which sometimes worked and sometimes didn’t. Soldiers trying to vaccinate themselves for smallpox would end up giving themselves syphilis as they contaminated one another. Confederates experimented with drugs and medicines as the Union blockade made their supplies run thin. One thing that worked more often than not was a change of diet. If a soldier came down with scurvy, a diet of fruit and vegetables was strictly adhered to – among other things. The same went for diarrhea.

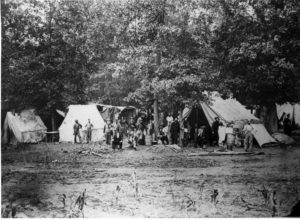

A field hospital at Gettysburg.

It is often said that more soldiers died of disease during the Civil War than from wounds received in battle. The rough estimates show this to be true.

Total Fatalities by battle: 204,100 (110,100 Union, 94,000 Confederate)

Total Fatalities by disease: 388,580 (224,580 Union, 164,000 Confederate)

Burial of Union soldiers after the Battle of Fredericksburg.

The next few weeks we will be exploring more about battlefield hospitals, medicine, surgeries during the Civil War. Our exploration of Civil War hospitals and medicines will culminate on March 12-13 with a special guided tour offered at the Tunnel Hill Heritage Center. We will be setting up our own Austin House Battlefield Hospital and reenacting what happened at a field hospital during this time. Stay tuned to our Facebook page and website for more details!