Have you ever seen a person glow in the dark? Maybe in today’s world it is not unlikely by use of fun body paints or glow sticks, but in the 1800’s this was a crazy idea. However, after the Battle of Shiloh, many wounded soldiers glowed when night fell after the battle’s end. This interesting phenomenon was called “Angel’s Glow” by the men who survived and told their stories. It wasn’t until 2001 when a 17-year old boy did a science experiment that the actual cause of this mysterious glow was discovered.

By the spring of 1862, Major General Ulysses S. Grant had pushed deep into Confederate territory along the Tennessee River. In early April, he was camped at Pittsburg Landing, near Shiloh, Tennessee, waiting for additional Union troops to meet up with him.

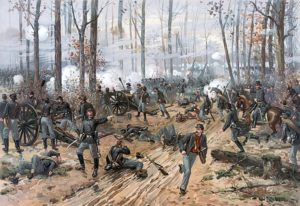

Shiloh Battle, April 6

On the morning of April 6, Confederate troops based out of nearby Corinth, Mississippi, launched a surprise offensive against Grant’s troops, hoping to defeat them before the second army arrived. Grant’s men, amplified by the first arrivals from the Ohio, managed to hold some ground, though, and establish a battle line anchored with artillery. Fighting continued until after dark, and by the next morning, the full force of the Ohio had arrived and the Union outnumbered the Confederates by more than 10,000. The Union troops began forcing the Confederates back, and while a counterattack stopped their advance it did not break their line. Eventually, the Southern commanders realized they could not win and retreated back to Corinth to plan a later attack.

The fighting at the Battle of Shiloh left more than 16,000 soldiers wounded and more 3,000 dead, and neither Union or Confederate medics were prepared for the carnage. It was over 48 hours before all the wounded were removed from the battlefield and given help. The bullet and bayonet wounds were bad enough on their own, but Civil War soldiers were prone to infections. Wounds contaminated by shrapnel or dirt became warm, moist refuges for bacteria, which could feast on a buffet of damaged tissue. As we have discussed in previous blogs, months marching, poor diets, and unclean living, many soldiers’ immune systems were weakened and unable to fight off infection. Many soldiers died from infections that modern medicine would be able to nip in the bud.

Battle of Shiloh – Thure de Thulstrup

The battle had taken place in a swampy area during abnormally cold temperatures, and many of the wounded lay in mud and foul cold water while waiting for help. After dark they noticed something odd: some of their open wounds had developed a faint greenish-blue glow. When the men finally reached field hospitals for treatment, the medics discovered something else odd. Soldiers who reported glowing wounds appeared to have a much higher survival rate than those who did not. The wounds that had glowed had less infection, and so they healed faster and scarred less than non-glowing wounds. No one had any explanation as to why this happened.

Fast forward to the 21st century, where “Angel’s Glow’ had become battlefield folklore. 17-year-old, Bill Martin, visited the Shiloh battlefield and heard about the glowing wounds. His mother was a research microbiologist for the US Department of Agriculture and studied luminescent soil bacteria. He asked whether such organisms could have caused the glow, and like all good moms, she suggested he should find out for himself.

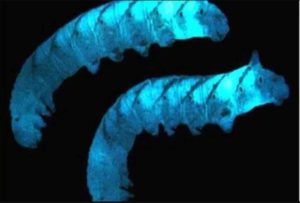

He and his friend, Jon Curtis, did some research on both the bacteria and the conditions during the Battle of Shiloh. They learned that Photorhabdus luminescens, the bacteria that Bill’s mom studied, live in the guts of parasitic worms called nematodes, and the two share a strange lifecycle. Nematodes hunt down insect larvae in the soil or on plant surfaces, burrow into their bodies, and take up residence in their blood vessels. There, they puke up the P. luminescens bacteria living inside them. Upon their release, the bacteria, which are bioluminescent and glow a soft blue, begin producing a number of chemicals that kill the insect host and suppress and kill all the other microorganisms already inside it.

Photorhabdus luminescens, the glowing nematode. Photo credit: Naked Scientists

Bill and Jon’s theory was that Heterorhabditis nematodes were drawn to insects in the soldiers’ bloody wounds. The bacteria they released made the wounds glow, while at the same time killing micro-organisms that might have caused gangrene or other wound infections. This explains the better survival rates and quicker recovery. A problem with the theory was that P. luminescens cannot survive at human body temperature. However, early April nighttime temperatures in Tennessee would have been low enough for the soldiers laying in the rain for two days to get hypothermia. Thus, lowering their body temperature and giving P. luminescens a good home until they were moved to the warm hospitals.

The saprobe Panellus Stipticus displaying bioluminescence

Turns out, the soldiers shouldn’t have been thanking the angels so much as the microorganisms. Bill and Jon earned first place in team competition at the 2001 Intel International Science and Engineering Fair. Pretty cool results after a trip to an old battlefield! A visit to the Tunnel Hill Heritage center may bring questions to your mind and maybe you could unravel a mystery from the past as well. We would love to have you visit us!