We know that nearly 300,000 black soldiers helped the Union cause during the U.S. Civil War. What is less well known is the role of a dedicated group of black doctors and nurses in uniform who worked diligently to save lives and fight disease.

The involvement of African Americans in medicine in the Civil War is an untold chapter in our history. Before the war, most doctors learned medicine by apprenticeship but this began to change in the early 19th Century. In 1837, James McCune Smith was the first African American to obtain a medical degree, he graduated from the University of Glasgow in Scotland. By the end of the Civil War at least 22 African Americans had obtained degrees and were practicing medicine. 12 of these physicians served with the Union Army. Three men were commissioned officers while the remaining nine served as assistant surgeons.

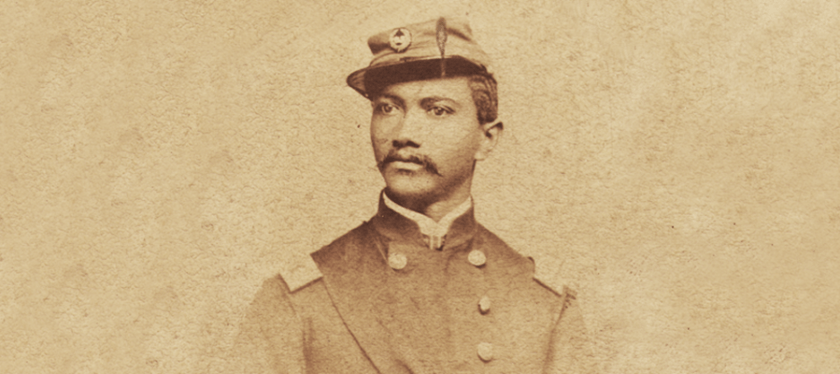

Lt. Col. Alexander T. Augusta

One of the most notable was Alexander Thomas Augusta. Augusta was born to free parents in Norfolk, Va. He began working as a barber and was taught to read by a preacher, something that was illegal and dangerous in the state. He dreamed of becoming a doctor, but that seemed almost impossible in the 1800s. Augusta moved to Baltimore and married a Native American woman, named Mary O. Burgoin. He applied to the University of Pennsylvania’s medical school, but his application was denied. Realizing he wouldn’t be accepted to an American college because of his race, Augusta travelled to Canada where he enrolled at Toronto’s Trinity College. After six years there he earned a degree in medicine.

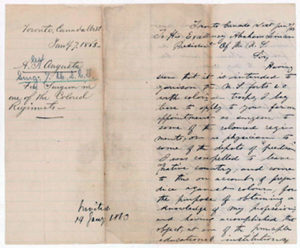

After graduating, Augusta went to Washington, D.C., where he wrote President Abraham Lincoln offering his services as a surgeon for the Union army. He was given a Presidential commission in the Union Army in October 1862. On April 4, 1863, he received a major’s commission as surgeon for African-American troops. This made him the United States Army’s first African-American physician and its highest-ranking African-American officer at the time. His pay of $7 a month, however, was lower than that of white privates. He wrote Massachusetts Senator Henry Wilson who raised his pay to the appropriate level for commissioned officers.

Jan 7, 1863 letter from Dr. Augusta to President Lincoln/ photo courtesy National Archives and Records Administration

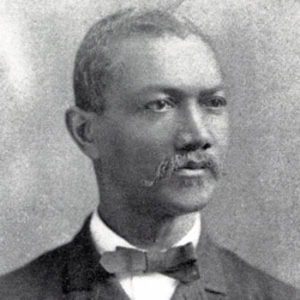

Augusta’s time in the Army was difficult both on and off the battlefield. Almost a century before Rosa Parks defied Alabama’s racial segregation laws, Augusta refused to give up his seat in the “whites only” section of a Washington D.C. streetcar. Dressed in his Union officer’s uniform, Augusta was physically ejected from the streetcar and beaten. He railed against this injustice in letters to newspapers and government officials. Soon after the incident, Congress decreed that all streetcars in the nation’s capital were to be desegregated. When his white assistants, also surgeons, complained about being subordinate to a black officer, President Lincoln placed him in charge of the Freedman’s Hospital at Camp Barker near Washington, D.C.

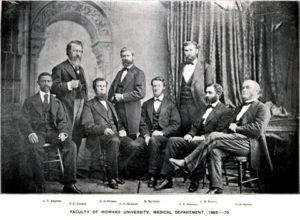

Howard University Medical College faculty, 1869-1870 with Augusta seated at far left/ photo courtesy National Library of Medicine

By the end of the war, he was made a lieutenant colonel for his hard work. When Howard Medical College opened in 1868, he was the only African American on its original faculty. Despite being denied recognition as a physician by the American Medical Association, Augusta encouraged young black medical students to persevere and helped make Howard University an early success. He later left the medical school for private medical practice in Washington, D.C. Dr. Alexander T. Augusta died at home four days before Christmas, 1890. Even in death Augusta broke the color barrier. Interred with full military honors, he became the first black officer buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Augusta’s Tombstone in Arlington Cemetery

This month’s blogs will continue to focus on medicine during the Civil War era, but we will also highlight the roles that African Americans held and how they contributed in honor of Black History month. This is all leading up to our special battlefield hospital tour on March 12-13. Check our events page to purchase tickets and make a reservation! We would love to see you at the Tunnel Hill Heritage Center.