For our final blog honoring Black History Month, we are going to step away from the Civil War medical history and learn about the 44th United States Colored Troops (USCT). It was an infantry regiment that served in the Union Army. The regiment was made up of freed African American enlisted men commanded by white officers. The 44th USCT was organized in Chattanooga, Tennessee by Colonel Lewis Johnson. Born on March 13, 1841, in Rostock, Prussia, Johnson served as a cadet in the Prussian navy for two years before coming to America in 1855. He enlisted as a private in April 1861, acquiring a commission of captain and wounds from two battles. He was from a family of writers, teachers, and printers, and thus Johnson encouraged his men both white and black to learn to read and write. The 44th regiment also became known as “the singing regiment” thank to the teachings of Rev. Lycurgus Railsback.

The regiment served garrison duty at Chattanooga, Tennessee, until late 1864. They saw battle action in Dalton, Georgia on October 13, 1864. 751 of the 800 regiment men were captured during this fight. 600 of these men, were free African American men, and were part of the largest surrender of African American soldiers during the war.

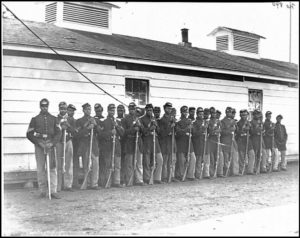

African American Civil War soldiers, 1865, Petersburg, VA

Contributed: Project Gutenberg

John Bell Hood’s campaign through North Georgia reached the edge of Dalton, a town his troops were familiar with because they had stayed in Dalton the previous winter. However, Dalton hardly resembled the town they had left when the Atlanta Campaign began: the town was mostly abandoned and had warehouses of supplies. The biggest difference was a garrison composed of a regiment of runaway slaves, the 44th USCT. This was shocking and outrageous to Hood and his men because many of these soldiers were escaped slaves from the North Georgia and Tennessee area.

Late in the morning on October 13th Hood’s Confederate Army of Tennessee approached Dalton and cut off all lines of retreat. The Union defenders which included the 44th USCT under Colonel Lewis Johnson barricaded themselves in Fort Hill. This was an earthen fort built upon high ground east of downtown Dalton. Below them a grim site developed as Confederate artillery deployed on heights across from them, and thousands of infantry filled in the space around.

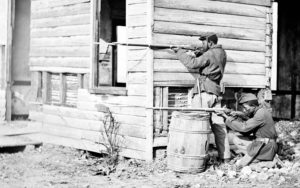

USCT at an abandoned farmhouse in Dutch Gap, Virginia, 1864

Confederate General William B. Bate’s and his men were assigned to capture the fort. A message was sent to Colonel Lewis Johnson.

“I demand the immediate and unconditional surrender of the post and garrison under your command, and should this be acceded to, all white officers and soldiers will be paroled in a few days. If this place is carried by assault, no prisoners will be taken. Most respectfully, your obedient servant, J.B, Hood, General.”

According to Bate’s records the offer was initially refused. After the refusal, Bate had his men fire several rounds into the stockade and shortly after a white flag was raised. Johnson really had no choice. His garrison of 751 men and two cannons were no match for the 20,000 men and 30 cannons of Hood’s that surrounded them. Colonel Johnson later claimed that his black troops showed the “greatest anxiety to fight,” they did not want to surrender. They knew that capture would bring them great hardships, such as being sold back into slavery or forced into labor for the Confederate army.

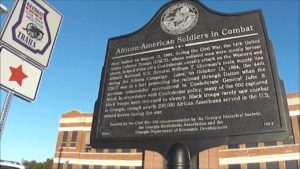

Erected by the Georgia Historical Society, the Georgia Battlefields Association and the Georgia Department of Economic Development

After surrender, Johnson secured paroles for himself and the 150 other white troops. The 600 African American men of the 44th USCT were not given the same treatment. At first, they were put to work tearing up parts of the Western & Atlantic Railroad. Private William Bevins of the 1st Arkansas remembered, “The prisoners were put to work tearing up the railroad track. One of the negroes protested against the work as he was a sergeant. When he had paid the penalty for disobeying, the rest tore up the road readily and rapidly.” Other cases of abuse occurred, and constant threats were issued forth as the prisoners were forced to move off with the army. Within days, notices were appearing in Southern newspapers announcing the capture of “negroes” at Dalton—they were never referred to as “soldiers”—and for the owners to come claim them. Some 250 were claimed and most like killed or tortured for having runaway. Of the remaining men a few managed to escape, some simply disappeared, and the rest were taken with the army to do a number of tasks, eventually set to work repairing railroads in Mississippi as the army moved into Tennessee.

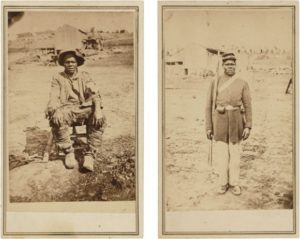

By December 1, 1865 only 125 men of the 44th USCT remained alive. The division mustered out of service April 30, 1866. Much remains unknown about the men who would have fought to the death at what we now call Fort Hill in Dalton, GA. We do know they were brave in the face of such hate and ultimately death for many. A plaque has been posted in their honor at the top of Fort Hill. Hubbard Pryor is a notable member of the 44th and his transformation is displayed in the pictures below. From slavery’s rags to the Union uniform of the 44th United States Colored Infantry.

Hubbard Pryor before and after enlistment.

Contributed: Records of the Adjutant General’s Office