On July 6, 1864, 400 Confederate prisoners of war marched from Erie Train Station to the camp, becoming the first of 12,123 prisoners held in Elmira. This camp quickly became known as “Hellmira”. It was overcrowded, disease was rampant, inadequate housing, and many other things gave it this name. It was the third prison camp opened by the Union army and perhaps the worst. Andersonville in Georgia, a Confederate army prison, was also famous for its poor conditions.

Living conditions were bad from the start. Proper shelter was scarce. The barracks held only half the prisoners; the others were crowded into tents, even in winter. A serious sanitary situation were the “bathrooms” better known as Foster’s Pond. It ran the length of the camp and was a cesspool of disease. Elmira was below the level of the Chemung River, which bordered it, making drainage difficult. After the harsh winter of 1864, the Chemung River flooded from the melting snow. This filled the tents and barracks with anywhere between six inches to two feet of water. Water that had feces and other waste in it.

Fosters Pond Looking West

The first contingent of prisoners arrived to find no doctor in the camp to provide for them, yet men suffered from dysentery and pneumonia. Sick prisoners lived in the barracks and tents with other healthy men, which only served to make more men sick. On August 6, Major Eugene Sanger, an army doctor, finally arrived at the camp. However, the Confederate soldiers were not fans of the doctor. He made some good changes but also some deadly mistakes. In one deadly instance, Sanger recommended treatment for three Confederates in failing health to one of his aides. Sanger prescribed “three or four drops of Fowler’s solution of arsenic.” Unfortunately, the aide neglected to include the word “or” when he wrote up the prescription. The three men each received 45 drops of the solution, and they all died. However, he did try to improve conditions in the camp by filing requests with the camp commanders, Colonel Benjamin Tracy and Colonel William Hoffman. Colonel Hoffman took months to approve the digging of a canal to get water from the Chemung River flowing through Foster’s Pond. This helped to alleviate some of the disease issues.

Map of Elmira drawn by Pvt. David J. Coffman, 7th Vir. Cav.

The winter of 1864-65 was particularly severe. The temperature fell below -18 degrees twice, the Southern prisoners were not use to such cold. They also lacked adequate clothing or housing. This was a huge shock to their Southern makeup. Colonel Hoffman would not allow clothing sent to from the South to be worn by the prisoners unless it was gray in color. Anything not gray was burned out of spite, while the men froze to death.

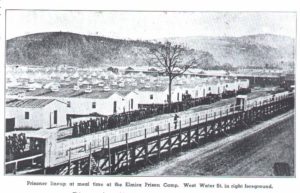

Prisoners lined up for mealtime.

Daily life in the camp was dull and the men would try to find ways to entertain themselves. Some would occupy their time by making trinkets out of animal hair or bone found around camp. The guards would take the trinket into town and sell them to children. Rats were also a valuable commodity. Prisoners would trade rats for tobacco or haircuts. The outside of the prison took on a festive type atmosphere. Two observatories were erected on the opposite side of Water Street during the summer months, and for 10-15¢, curious onlookers could view inside the camp. Prisoners, unhappy about being gawked at, would sometimes perform derogatory type circus acts. Other opportunists opened food and beverage stands for people to have refreshments while watching the starving prisoners. In September, the army took possession of the area and dismantled one of the towers. The other tower remained open though business declined due to the encroaching cold weather, and onlookers began to realize the harsh reality of what they were paying to see.

Original Flagpole Location Marker

While some prisoners spent their time trying to entertain onlookers or making trinkets to sell, others passed the hours by plotting their eventual escape. In total, there were fewer than 20 escapes. One small group endeavored to dig a 66-foot tunnel using spoons and knives. Their dig to freedom was successful and they made it back to the South. The other successful escapes were varied and creative. One man forged a pass and walked out the gate; another stole a sergeant’s overcoat and strolled out. In a most morbid escape plot, one man had his friends loosely nail him into a coffin. He was carted out of the prison to the graveyard, only to leap out and scare the driver on the way to his burial.

Artillery on guard over the prisoners at Elmira. This was because of the prisoners escaping by tunneling out.

Over 2,900 of the 12,100 Confederate prisoners housed there from July 1894 – July 1895 died from disease, malnutrition and harsh winter conditions. That is close to a 24% death rate. Not too much less than the famed Andersonville prison’s rate. The camp was officially closed on July 5, 1865. You can still visit the prison site in Elmira, NY. An original outbuilding survived and has been reconstructed, along with a recently built barracks that were created with the aid of original drawings and photos. Next week’s blog we will dive into Andersonville prison!