Grover Cleveland, future President of the United States, never served in the military during the Civil War. He was healthy, of the appropriate age, and educated. His law practice provided him a comfortable living. John D. Rockefeller living in Cleveland, OH was also healthy and eligible to serve in the armed forces of the United States. Yet, he did not serve in the Union army during the Civil War. Many healthy men who were eligible to serve in the military during the Civil War never ended up enlisting. The Enrollment Act of 1863 provided that a draftee could pay a “substitute” enrollee the sum of $300 (about $5,000 in today’s terms) in order to enlist in his place. Such famous Americans as Grover Cleveland and John D. Rockefeller took advantage of this provision, in effect buying their way out of service.

All Union men between the ages of 20 and 45 were required to sign up to fight. Each recruiting district had quotas to meet, and those districts where numbers fell short would draft soldiers by lottery. When names were selected from the lottery, men had two options: fight or pay someone to take their place. Of the more than 750,000 drafted in 1863 and 1864, only about 46,000 actually saw battle. The remaining 85% avoided the war by literally running away or paying someone to fight in their place.

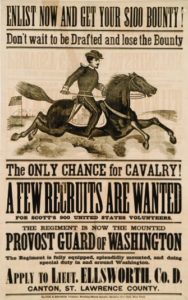

Civil War recruiting posters included bounty incentives.

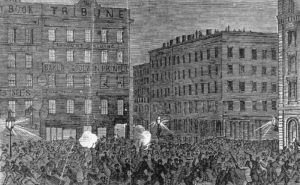

This prompted many in the Union to believe that the Civil War was a “rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight.” In July 1863, tensions reached a highpoint during the New York draft riots where African Americans, resented for causing the war, were targeted with brutal violence. At least 120 people were killed in the five-day brawl, which remains one of the deadliest episodes of civil unrest in American history. The draft reflected a shift in the perception of the war from a patriotic duty to a burden. This view was also strongly seen during the drafts for the Vietnam War. Unfortunately, the war would require more than two grueling years and four separate drafts before the end was in sight.

Rioters attacking the offices of the New York Tribune, a leading Republican newspaper, during the Draft Riot of 1863.

Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

This new system was also riddled with fraud. Professional “jumpers” would take the substitution payment, desert their units before they left for the front, then repeat the process. Officers would complain about seeing the same men arrive with new recruits multiple times.

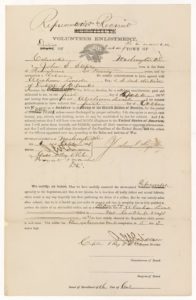

Even Abraham Lincoln used a draft substitute. He was too old for the draft, however being president, would have exempted him regardless of age. But the Army was short of men, and the commander in chief wanted to encourage other “ineligibles” like himself to voluntarily hire a substitute. To that end, in 1864 he paid a “representative recruit” to fight for him. This document, held in the National Archives, records the enlistment of 19-year-old Pennsylvanian J. Summerfield Staples at Lincoln’s request.

National Archives

Staples, who had served as another man’s substitute earlier in the war, was walking down Pennsylvania Avenue when he was offered the new job. The president had assigned Noble D. Larner, a member of the draft committee, to find a suitable recruit. Larner bumped into Staples on the street. After Staples said he might be interested in the job, Larner took him to the White House. There, Lincoln approved of Larner’s choice, told Staples he hoped he’d be “one of the fortunate ones,” and paid him $500. Staples had a pretty easy time of it in the Army; he served for only a year and worked as a clerk and a guard.

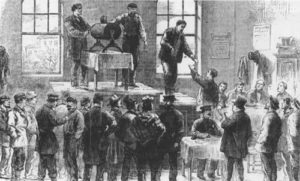

Conscription at a New York City Draft Office.

It was the Confederates, however, who had resorted to a draft first, in April 1862. All healthy Southern white men between ages 18 and 35 were required to serve three years (ultimately, this would be extended to men between ages 17 and 50). The most controversial element of the Confederate conscription was the “Twenty-Slave” law, which allowed one white man from a plantation with 20 or more slaves to avoid service during the war. This was in part a response to the pleas of many Southern women, who were unprepared for and overwhelmed by the responsibility of running plantations on their own and managing a significant number of slaves. As in the North, many Southern farmers cried that this was “a rich man’s war but a poor man’s fight.”

Bounty Brokers Looking for Substitutes

Library of Congress

Nevertheless, in both North and South, statistics indicate that wealthy men were represented in the service in at least the same proportion as they were in the general population. In the end, the Civil War draft produced much more animosity than men, effectively functioning as a tax more than as a way to raise armies. The Selective Service Act of 1917, instituted following an extreme shortage of volunteers for World War I, proved far more comprehensive and successful. By the end of the Vietnam War, widespread opposition to the draft lead to its repeal. The last men were conscripted in December 1972.