An ill-mannered man with streaks of wildness, nonconformity, and sometimes drunkenness. Battered, beaten, discredited and a hopeless cripple. No evidence of mental brilliance. History has not been kind to John Bell Hood. A military career marked with early victories unraveled when Hood took the reins of the Army of Tennessee as the Confederacy tottered towards destruction. Today’s blog we discuss his career and brief stay in Tunnel Hill.

John Bell Hood was born June 1,1831 in Kentucky. His father was a wealthy slave owning doctor. Hood didn’t follow his father’s footsteps and instead secured a position at West Point. As a student, Hood had less than stellar grades, earning average marks in many of his classes. Some people think that Hood’s average performance at West Point foreshadowed his eventual military disaster. In the end, Hood graduated ranked 44 out of 52 remaining cadets in 1853.

Lt. Gen. John B. Hood

After graduating, Hood accepted an appointment with the 4th Infantry Regiment and spent time in California before he snatched a coveted position with the newly formed 2nd Cavalry guarding the Texas Frontier. At the end of 1860, West Point offered Hood the chief of cavalry at the Military Academy. However, with rumors of secession across the South, Hood turned down the prestigious appointment. Returning to Kentucky, he was disappointed that his native state failed to embrace secession. Thus, he adopted Texas as his new home state, which eventually garnered him command of the 4th Texas Infantry.

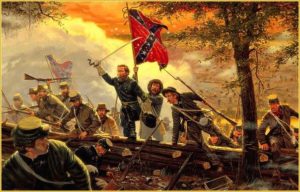

Hood commanded the Texas Brigade in many brutal fights throughout 1862 and 1863. At Gaines’s Mill, Virginia on June 27, 1862, Hood led his men in an assault leaving many causalities but finally helped General Robert E. Lee remove the Union army from the outskirts of Richmond. A few weeks later, at Antietam, Maryland, the Texas Brigade attacked again and drove back the Union advance. Once again, Hood’s men paid a heavy price in order to prevent a Confederate disaster. Hood’s strong, aggressive command skills and his men’s bravery, earned him a promotion to Major General on October 10, 1862.

“Desperate Valor,” depicting Hood’s Texas Brigade at Gaines Mill, by Gallon Historical Art

On July 2, 1863, while fighting in Gettysburg, PA, fragments from an artillery shell struck Hood in his left arm. His arm was permanently mangled, and although intact, it was useless for the rest of his life. Private John C. West wrote:

“I believe the wounding of General Hood early in the action was the greatest misfortune of the day.”

Hood recovered in Richmond, Virginia, where he made quite the impression on the ladies of the Confederacy. In August 1863, famous diarist Mary Boykin Chesnut wrote of Hood:

“When Hood came with his sad Quixote face, the face of an old Crusader, who believed in his cause, his cross, and his crown, we were not prepared for such a man as a beau-ideal of the wild Texans. He is tall, thin, and shy; has blue eyes and light hair; a tawny beard…. the whole appearance that of awkward strength. Someone said that his great reserve of manner he carried only into the society of ladies.”

Hood rejoined the Confederate army just in time for the battle at Chickamauga, Georgia in mid-September, 1863. As Hood rode along the lines commanding his men, a minié ball smashed through his right femur, ending Hood’s command of his Texas Brigade in battle. Hood’s condition was so grave that the surgeon sent the severed leg along with him in the ambulance, assuming that they would be buried together. He underwent an amputation four inches from his hip, an operation with an 80% death rate. Yet, Hood lived to fight another day, despite numerous reports of his death. He recovered for a brief time at the Clisby Austin House here in Tunnel Hill, Ga. We have a mini memorial to his leg as well, since he survived it was buried somewhere most likely on our property.

Hood’s leg memorial in Tunnel Hill, Ga.

Hood returned to Richmond for a second recuperation. He befriended Confederate President Jefferson Davis, who would subsequently promote him to a more important role. He also fell in love with Sally “Buck” Preston. Hood confided to Mary Chesnut that the courtship “was the hardest battle he had ever fought in his life.” In February, Hood proposed to Buck, who was playing hard to get. She reluctantly agreed. However, the Preston family did not approve of Hood. So, he left for the field unmarried and heartbroken. Hood was appointed as a corps commander under Joseph Johnston with the Confederate Army of Tennessee.

Jefferson Davis requested that Hood keep him informed of Johnston’s actions as a commanding general. The Army of Tennessee had to protect the vital transportation center of Atlanta, Georgia. Hood commanded from the saddle, with a prosthetic wooden leg dangling from his horse. Hood wanted Johnston to move back and re-take Chattanooga. However, Johnston remained in Dalton, Georgia until May, 1864, when Union commander Major General William Tecumseh Sherman launched an offensive from Chattanooga towards Atlanta.

John Bell Hood (circa 1864).

As Sherman advanced, Johnston withdrew from Dalton to Resaca in order to prevent his army from being flanked. After a brief skirmish, Johnston strategically withdrew again, a pattern that persisted for the next several days. Both Hood and Johnston later claimed they wanted to attack Sherman. Neither Johnston or Hood were able to defeat Sherman and Atlanta fell to the Union army. Hood resigned as head of the Army of Tennessee on January 23, 1865. He thanked his men for their service during the campaign and returned to Richmond, Virginia. President Davis asked him to head west to Mississippi and gather any possible men to keep the war effort afloat. Hood headed west but eventually surrendered to Union forces at Natchez, Mississippi on May 31, 1865.

After the war, Hood moved to Louisiana and became a cotton broker and had a successful life insurance business. In 1868, he married New Orleans native Anna Marie Hennen, with whom he had 11 children over 10 years, including three pairs of twins. He also served the community in numerous philanthropic endeavors, assisting in fund-raising for orphans, widows, and wounded soldiers. Hood began a memoir, Advance and Retreat: Personal Experiences in the United States and Confederate States Armies. He died before completing it. His memoir served to justify his actions, in response to what he considered false accusations made by Johnston, and to his unfavorable portrayal in Sherman ‘s memoirs.

Yellow fever struck the city of New Orleans in August 1879, killing Hood, his wife and eldest daughter in one week. The Texas Brigade Association provided support for the remaining orphaned children. All ten were eventually adopted by seven different families. John Bell Hood is interred in the Hennen family tomb at Metairie Cemetery in New Orleans. Hood’s descendants, still alive today, serve as a powerful living monument to a Civil War personality who experienced triumph and tragedy during America’s most critical hour. At the end of his life, General John Bell Hood was regarded by most as a well-respected soldier who had risked life and limb for his country. On June 18-19, we will have a living history tour with General Hood. See him in action recovering from the loss of his leg.

Grave of John Bell Hood.