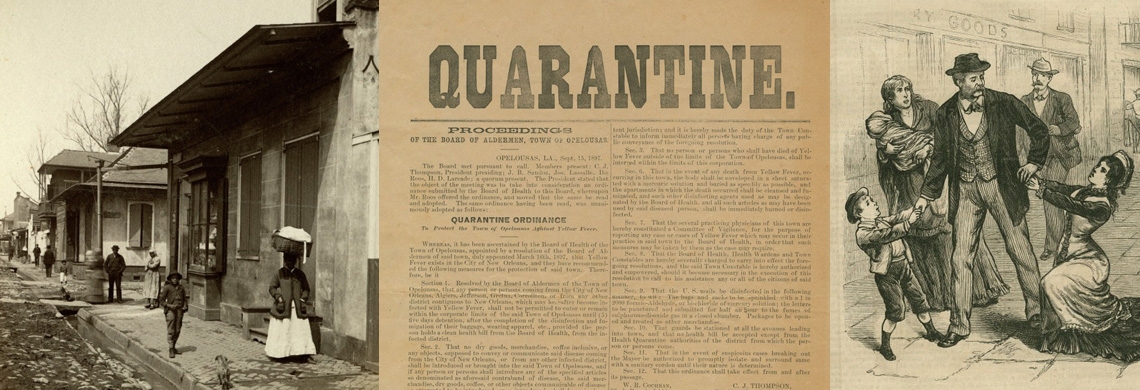

The quarantine or “stay at home” order we lived under during April of 2020 may have felt new to us, but it wasn’t the first time that a mandatory quarantine has been put in place to help protect disease from spreading. Yellow fever was a major problem in the South, killing over 10,000 people. There were more outbreaks in Texas during the Civil War than in any other state. Epidemics occurred in summer and autumn months. It was commonly referred to as “stranger’s disease” since it most often affected those new to the area. The people that were infected and survived acquired lifelong immunity. Outbreaks would often occur after a ship arrived from a Caribbean port. It could be prevented by quarantining newly arrived ships in most cases. Attempts at its prevention by Union General Benjamin Butler in New Orleans may have been the first example of a medical incentive plan.

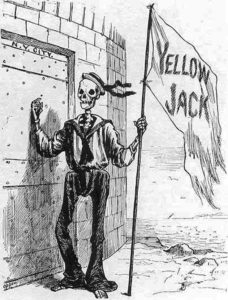

Death as a sailor bringing Yellow Fever to New York

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper

General Benjamin Butler or the “Beast” as the locals referred to him was greatly loathed in New Orleans. Butler’s behavior as the commander of Union forces in New Orleans for only eight months in 1862 spawned an evil, enduring reputation among southerners that was rivaled during the Civil War only by that of Gen. William Sherman after his fiery march through Georgia.

Major General Benjamin F. Butler, circa 1860–1865

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

From the start, New Orleans citizens treated Union soldiers with contempt and scorn. Women, in particular, verbally abused troops, sang secession songs in their presence, and worse. Troops were spit on and chamber pots were dumped from balconies onto passing soldiers. The weakening situation prompted Butler to issue his infamous General Order No. 28, which read:

New Orleans, May 15, 1862. As the officers and soldiers of the United States have been subject to repeated insults from the women (calling themselves ladies) of New Orleans in return for the most scrupulous non-interference and courtesy on our part, it is ordered that hereafter when any female shall by word, gesture, or movement insult or show contempt for any officer or soldier of the United States she shall be regarded and held liable to be treated as a woman of the town plying her avocation.

The perceived insult spread across the country and the Atlantic Ocean like wildfire. In the South, nothing was more sacred than the honor of a woman. The order was also unpopular in the North. It was eventually a factor in Butler’s removal.

“Women Before Butler’s Orders and Women After Butler’s Orders” Harper’s Weekly, July 12, 1862

Butler’s job in New Orleans was unenviable. Thousands of citizens, including slaves, were hungry and without means of support. It lacked a functioning government; the city was filthy and ripe for epidemics of infectious disease. Crime was rampant; seditious behavior, including the threat of assassinations and smuggling, was everywhere. While New Orleans hadn’t had a major outbreak of Yellow fever in years, citizens used their own form of fear mongering to make the Federal troops complain and worry about staying in the city. Butler responded by setting up a checkpoint on the outskirts of the city along the Mississippi. Every ship was tested for yellow fever and if they were found to have just one sick person, the ship was quarantined for 40 days. It was thought after the 40 days; a contagious disease would die out.

Butler, told Dr. Jonathan M. Foltz: “In this matter your orders shall be absolute. Order off all you may think proper [ships to quarantine], and so long as you keep yellow fever away from New Orleans your salary shall be one thousand dollars per month. When yellow fever appears in this city your pay shall cease.” Dr. Foltz quarantined all ships for 40 days 70 miles below the city, and this virtually eliminated yellow fever in New Orleans. In recent years, around 10% of the city’s population would die from Yellow fever. Under Butler’s leadership in 1862, only 2 cases were recorded.

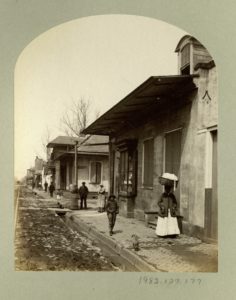

New Orleans was one of the largest, smelliest, and deadliest cities in the United States. The city’s gutters, drainage canals, and streets were littered with refuse, including garbage, food waste, and human and animal waste. Dirty, stagnant water could be found everywhere. This was a large reason why disease ran rampant in the city. Seeking to obstruct every avenue for an outbreak, Butler hired eleven hundred local men and put them to work cleansing the city of animal waste and human excrement. The waste stood in two feet deep in some places! New basic sanitation regulations were put in place on the locals and compliance was enforced by weekly inspections from one of Butler’s inspectors. Butler’s guidelines were so strict, that when one infected seaman managed to slip into the general population, the quarantine that followed was so complete that no one else was affected.

Street-side drainage gutters, like the one in this image, were littered with refuse, and dirty stagnant water could be found everywhere.

While he worked at cultivating the support of the population through relief spending and public health initiatives, Butler never forgot that his foremost role was that of a military occupier in hostile territory, reminding the citizenry that “the same hand that cuts your bread can cut your throat.” Even though the community improved by leaps and bounds, no New Orleans citizen liked Butler any better for it. He was still a Yankee, after all, and his “beast” attitude earned him no love.

Despite his harsh ruling and everyone hating him, General Benjamin Butler helped pave the way for a method of strict cleanliness and quarantine standards that are still used today. Perhaps he was more of a friend than a “beast”, despite how he’s remembered. It is interesting how often history will repeat itself or how old solutions might work in today’s world. We will continue to explore that and more in the next blogs and then join us March 12-13 for a special behind the scenes look at a Civil War battlefield hospital.