Nursing was not a woman’s job before the Civil War, but by 1865, there were over 3,000 nurses serving the Union and Confederacy. In the North, most female nurses worked in military hospitals. African American women serving as nurses were not included in those numbers, nor were they recognized for their service for decades to come.

Black nurses with the 13th Massachusetts Infantry Courtesy: National Library of Medicine

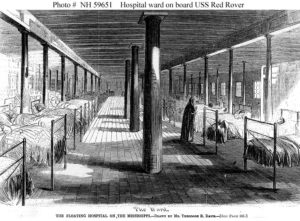

It is a largely untold story but during the Civil War, black women did serve as nurses. The United States Navy had several African American women serve as “first class boys” on the Union hospital ship U.S.S. Red Rover. “First Class Boy” was a rank given to young men under seventeen who performed general sailor duties. Ann Bradford Stokes is the most well-known of these women and today we will explore her story.

In 1830, Stokes was born into slavery in Rutherford County, Tennessee. Not much is known about her early life except that she was unable to read or write. In January 1863 she escaped her plantation and ended up hiding along the Cumberland River. She was captured and taken aboard the Union ship, the U.S.S. Red Rover as “contraband” (an escaped slave). Luckily for Stokes, Lincoln’s signing of the Emancipation Proclamation changed her from an escaped slave to a free woman. If she wanted, she could leave the ship. Hungry, homeless, and vowing never to return to the plantation, she chose to stay on the ship and make a life for herself. She signed on as a volunteer with the Sister of the Holy Cross of Notre Dame, who were nurses acting under the governor of Illinois’ orders. Stokes became the first African American woman to serve on board a U.S. military vessel, and she was among the first women to serve as a nurse in the Navy.

U.S.S Red Rover Navy Hospital Ship

Courtesy: U.S. Navy

For the first time in her life, Ann Bradford Stokes was a paid worker. Stokes and four African American women (also escaped slaves) cooked, cleaned and laundered. Most of their time, however, was spent nursing the wounded or sick. Lacking professional training in medicine, the women relied on their insight and folk remedies learned on the plantations. The women endured horrifying conditions while serving on the Rover. The summer heat from the Mississippi was dreadful. It came with an overwhelming humidity, haughty flies and mosquitoes who buzzed incessantly around the infected wounds. Bandages oozed with blood and pus, emitting a rancid stench that was unescapable. No matter how much they washed the floors or aired out the ward, the smell remained. For 18 months, Stokes and the other nurses cared for almost 3,000 wounded under these conditions.

She stayed on active duty until October 1864 when she was too exhausted to carry on and resigned her position. After leaving the Navy, Ann married Gilbert Stokes, who had also been employed on the Red Rover. The young couple moved to southern Illinois, but two years later, Gilbert died. In 1867, she remarried George Bowman and together they had one child. In the 1880s, she applied unsuccessfully for a pension based on her marriages to Stokes and Bowman. Her pension application was very difficult because of her inability to read or write. It was also denied because she was applying based on her husband’s services instead of her own.

Stokes was not deterred. In failing health, she learned to read and write, and in 1890, reapplied for her pension. This time, she laid out a different argument: She wanted the pension based her own service aboard the Rover, not her deceased husbands. It was a brilliant move, one that blindsided the pension office. They asked the Navy to review her case. The Navy decided that since Stokes served eighteen months as a “boy” in the United States Navy, that she was deserving of a disability pension. In 1890, Stokes was granted a pension of $12 a month which was the amount usually awarded to nurses at that time. This made her the first woman to apply and be granted a pension based on her own military service. Ann passed away in 1903 and left quite the legacy.

Our Heroines, United States Sanitary Commission

Harper’s Weekly, April 9, 1864 by Thomas Nast

Ann Bradford Stokes was extraordinary in many ways. She was one of the first women ever enlisted as active duty personnel in the United States Navy. In addition, although some 15 African American women were enlisted in the Navy at that time, she is the only one who is known to have applied for a pension. Most remarkable, she received that pension based on her own military service rather than that of her husbands.

Join us next week as we discuss the accomplishments of Susie King Taylor, another infamous African American nurse. And don’t forget that March 12-13 will be our special Battlefield Hospital Tour! You will get to see a live reenactment of a battlefield hospital similar to the ones these women would have worked in.